April 2022

Alcio Braz is a zen teacher in Brazil. In a recent talk to the Upaya community, he spoke of blending zen with Brazilian cultural practices and beliefs. This felt like something Creative Dharma subscribers might find interesting, so editors Brad Parks and Ramsey Margolis caught up with him.

However … this newsletter, our 15th, is most likely our last. While we are going to miss the process of creating it, and we hope you may miss reading Creative Dharma, here we offer an invitation to each of our 435 subscribers:

If you have the time, energy and inclination to continue breathing life into this project by taking the reins and moving Creative Dharma on into our common future, please reach out and make us a proposal. Reply to this email – we would very much like to see this labour of love develop in unexpected directions. ⁂

Find out more at the end of this newsletter.

A CONVERSATION WITH ALCIO BRAZ

Practising magic – Zen in Brazil

Stepping into a Rinzai temple in Tokyo in 1992, Brazilian psychiatrist Alcio Braz became a dharma practitioner. Ordained as a zen priest in 2001, he is now head priest and teacher at two sanghas – Einiji in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Togekkoji in Lisbon, Portugal.

With Native Indian Fulani-Ô, Portuguese and African ancestors, Alcio was born in Rio de Janeiro, worked as a psychiatrist in the Brazilian public health system, and now retired he works for NGOs and in private settings. He holds a Masters in social anthropology.

⬆︎ The altar at Einiji Zen Temple, Rio [photo Alcio Braz]

Creative Dharma ❖ During your Upaya talk you asked: ‘Can the dharma really flourish in our own land if it does not become native?’. In this newsletter, we’ve been looking at an approach to the dharma in which dharma practitioners are developing a creative approach to practising meditation, and creative artists bring a meditative sensibility into their creation of art, and how they relate.

For instance, in Aotearoa New Zealand there’s a very strong sense of Māori culture. Māori people had been very much oppressed for a long time, but they’ve been gaining strength and confidence over the past few decades, so that the English spoken in the country today is a blend of te reo Māori and English. It really feels lovely, and creates a strong sense of difference from other speakers of English. As dharma practitioners, we discuss how we might introduce indigenous practices into our practice; so how have you been bringing native Brazilian and Afro-Brazilian practices into your zen practice?

Alcio ❖ Buddhism really came to Brazil after the second world war; the Japanese migrants before that point had kept their religion to themselves. Up to the second world war, Brazil had been very much influenced by European, mainly French, culture. After the second world war, we were massively invaded by North American culture: English songs, everything that the Americans did. This happened all over South America.

So when Americans became influenced by zen and Tibetan Buddhism, these came here too. In the sixties, Japanese and Tibetan teachers arrived, but very few – not like the flow to the USA or Europe. Most missionaries saw being sent to South America as more of a punishment, and Buddhism became a phenomenon of a middle class who could afford marijuana experiences, dharma experiences, new age experiences, everything like that.

In 1964, there was a military coup d’état in Brazil. As in all of Latin America, it was stimulated by the CIA to counter communist influence. Religion then became an important way of identity construction, since all others were forbidden. You couldn’t go into the world of politics, so religion became a major way of escaping. As did, in a minor way, psychoanalysis for the very small part of the population who could afford it.

We imported the whole package – in the sense of Japanese culture, or Tibetan culture. It was cool to feel, ‘Ah I’m a Buddhist. I can speak a little Japanese, some words that nobody understands, and I go to exotic rituals.’ This was valued by the middle class, while native Afro-Brazilian and Native American cults were for poorer people. If you wanted some kind of status, you did the Buddhist thing, which was better than the Catholic thing because Catholicism was the tradition of our parents.

My father, though, was a priest in the native Brazilian religion, so I was exposed to this religion when I was a kid: spirits, possession by old Indians who were good, and more. He would put me on his lap when he was possessed, giving consultations to people who looked at him as a doctor, though actually he’d been in the merchant navy.

I loved it, because usually he was not very affectionate, mainly rude. When he was possessed by this wise Indian, he was very tender, a nice person. I would ask my mother, ‘When will father be possessed again?’

My upbringing was not very middle class in that we were not ‘upper’ middle class. Indeed, my father was arrested during the military coup era because he was a leftist, so we were behind a social barrier as it were.

CD ❖ Was your father in prison for a period of time?

Alcio ❖ Yes, for a year, but he came back. Because of his religion, he had friends everywhere. That’s funny, because while most people wouldn’t acknowledge links to native religions, they’d go to them when in need, and he had a network of friends in prison. This saved him from being killed. One day he was taken from our home by the military, and one day he came back.

Today, I think it’s funny, but we had a very conflicted relationship when I was a kid. I always went to bed late, and said, ‘Please God, kill my father, kill my father’. And then when he was in prison I felt guilty. I thought, ‘Oh God, what I said was not true’.

CD ❖ But it’s lovely that you had that relationship with him when he was possessed by the wise, old Indian.

Alcio ❖ Yeah. The funny thing is that while my mother was descended from Indians, my father was totally Portuguese, and yet he’d become a priest in the native religion. This is part of the confusion we call Brazil, and that’s fine.

My mother was the granddaughter of Indians. She was Catholic, but Catholic in the Brazilian way which mingles it with a lot of Indian elements. It’s not like being Catholic in Rome, it’s something very magical. So magic was here from the beginning.

⬆︎ A native religion altar, with food [photo Alcio Braz]

When I went to medical school, I was already involved in a lot of religious things. For some years, they tried to indoctrinate me in rational ways of medicine, but they didn’t succeed. I later became interested in Buddhism, and many other things, but never quit the religion of my family and friends. I was initiated in the native religion as well as baptised in the Catholic religion of my mother. I still go to church, I still go to Mass, I like it. Some people say that I’m very pragmatic about meeting somebody when I die, but who knows who?

So, at some point I went to Japan, and when I came back to Brazil I was ordained by a Japanese priest.

CD ❖ You were in your thirties when you went to Japan, weren’t you?

Alcio ❖ Yes, 32 or 33. I began practising at Sounji temple in Tokyo. The monk there was a very nice person. Then, when Tokuda Roshi came to Brazil, he was very respectful of Brazilian traditions. He even made some kind of sessions with a priestess of Candomblé, for his health.

Buddhism makes this kind of cohabitation easier because it’s very open – there are no real gods, but many deities. It’s not a closed system – ‘ah this is a Buddhist state, that is not’. After a while I began to think, ‘why not be open to the fact that all of us practice two religions at the same time?’

CD ❖ Is this what you refer to as the ‘real’ globalisation of the dharma?

Alcio ❖ Yes, because in that sense I think the dharma is much more a way of being alive. I understand the dharma as a way of being really present in this room, in this life. But I also understand that each of us has their own tradition, their own family, their own language. And I think the dharma manifests itself, for example, as the old Indian who spoke through my father.

When I give a dharma talk I say that, at that point, I’m a horse for the dharma, because in the Brazilian native religion we say that priests are like horses for the dharma. It’s not the dharma for the spirits, in the sense that spirits mount on you, and speak through you – they use your voice, but it’s not you, it’s the spirit that’s speaking. I never remember what I say. I listen to it later.

So if we use the word ‘possession’, I would say that I’m possessed by the dharma. That’s not very orthodox, but I think this is how the dharma manifests. It can manifest as old Indian spirits through my father, it can manifest through what they call the old, wise black man – a very respected figure here; it’s called in Portuguese preto velho which means a very old black man who gives his advice to people in rituals.

These religions were the way that the culture of the people here could survive oppression and genocide. Now, those religions are sought out by people who are mostly descendants of the oppressors. It’s not vengeance; it’s the possibility of real peace, in the sense that we are the result of this mixture of everything.

Right now, there are a lot of people on the extreme right in Brazil. If 20 percent have far right thinking, this is 50 million people. It’s very dangerous because most of them became evangelicals. They are fanatical people, not like Presbyterians or Methodists.

CD ❖ Are they possessed by a spirit too?

Alcio ❖ Yeah, and they talk a lot about the devil. I’ve gone to some of their services to try to understand them better. They talk ten times more about the devil than about Christ or anything good. It’s very dangerous, because those people attack native religions and are associated with the very far right government. Some are intelligent, and I would say these are the strategic thinkers, but most are very dumb – maybe like the people who went to Capitol Hill on 6 January 2021. Bolsonaro took a lot of his leads from Donald Trump, it seems.

When I saw the images of the Capitol Hill invasion, I thought, ‘Oh, my God, they’re having a taste of what we’ve been tasting for the last 50 years’. The CIA was behind every invasion of the Congress here in Brazil. My goodness, that’s karma.

CD ❖ How do you interpret the meaning of a Buddhist words, or teaching such as dukkha, dharma, making them relevant for the community you teach?

Alcio ❖ Or karma, for example. What is karma in Brazil? We’ve lived in a society that has had systematic genocide for the last 500 years. Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president, is a result of this karma. I don’t think someone is counting actions and saying, ‘Oh, they deserve a Bolsonaro’. No, I think it’s the building of karma: the last 500 years since our society began with this invasion by the Portuguese, and then people began exploiting each other in that sense.

CD ❖ Kind of like predictable consequences of actions over time?

Alcio ❖ Yeah, that’s karma, and I think we can transform karma into dharma in the sense that we must find a way to to transform things without hate. I’ve seen so much hate here. It doesn’t work.

⬆︎ Home altar [photo Alcio Braz]

CD ❖ Could you say something about the connection between ego and culture?

Alcio ❖ I think ego is something that is necessary, because when we call ourselves Brazilians, that’s part of the ego thing. I mean, identity, in the sense of tradition. This is the positive part of the ego, the part that can take us to the temple, that can make the decision to practice, that can even make the decision not to give so much importance to yourself. But when the ego becomes the most important thing, it becomes the foundation of capitalist accumulation, along with nationalism in its worst aspects.

The practice of the dharma helps us see this and may enable us to make an international peace movement. Joan Halifax, roshi for the Upaya community, called me to steward a group during an engaged Buddhist training. I’m the steward of a group of twenty people, mostly American. We felt a conviviality from being together, but then we began to see that although we were from different cultures, and some even from American Indian culture, we could find a common ground in our practice, a common ground of compassion, goodwill, a comprehension of our fragility and vulnerability.

Practice of the dharma offers the possibility of transcending the darker side of the ego. We have a brighter side of the ego that makes us able to talk here and be together. Sometimes I joke with Joan: I tell her it’s very interesting that I can talk with you in English, but you cannot talk with me in Portuguese. Portuguese is the language of the oppressor, it’s the language I have to speak because our language was destroyed in the course of the colonisation. Now it’s being rebuilt, but still a very small number of people speak Indian languages in Brazil, because it was totally forbidden for 200 years.

My parents couldn’t speak it, I can’t speak it really – I know some words, but it’s not my language. But I can speak English because my mother told me, ‘You should study English because if you want to connect with people in other parts of the world, you cannot speak only Portuguese because you’re gonna be lost’.

CD ❖ During your talk at Upaya you said, ‘Generosity, effort, care and compassion – these are the spirit of zen’. Can you say something about that in a multicultural context?

Alcio ❖ That’s very important, because when people imported the idea of zen from Japan, it came with Japanese masters. But more than Japanese masters, there was an idealised imagination of what zen is, and this imaginary zen included a lot of keisaku hits. And there were enigmatic words – the more enigmatic the master was, if nobody understood him, the guy was thought to be wonderful.

So at some point, we began looking around us and seeing people being oppressed and dying and poor and hungry. I asked, ‘What are we practising, really?’ Are we practising something that makes us more human, or something just to take us out of our situation. Because the problem is that techniques, like meditation techniques, were looked upon as something that makes us better than those people who are around us. So it becomes arrogant, and not only arrogant but chauvinistic, because we supposed they didn’t know how to deal with their anger, their difficulties.

When you look at the Buddha, you see a compassionate person. He took care of the sores of a monk that nobody wanted to be near, and said that was the real dharma. Of course, I would say that meditation and zazen are very good, but it’s only good when connected with other practices. I like what Dogen Zenji says: that when you practice zazen, compassion comes naturally. I understand him, in the sense that if we begin to understand how nothing we are, we can become something in connection with other people, because we are fragile, and can make a network of people.

⬆︎ Alcio Braz at home with friends [photo Alcio Braz]

CD ❖ You also said that, ‘the Buddha came back from the forest to teach people how to care for each other’. Could you expand on this please?

Alcio ❖ Yes, that really moves me. The Buddha cared for people, and that’s the core of our practice. Even if you are in devotional practice, like reciting ‘Namu amida butsu’, or the heart sutra, it’s okay. But where’s your contact with people, and what’s the point of sitting in zazen? Dogen said, ‘Even frogs sit quietly for hours’.

CD ❖ You spoke about life in the kitchen, nourishment and the preparation of food, being together to make something happen. Zen can be so austere – black robes, an aesthetic of simplicity, with everything stripped down to almost literally nothing. You describe indigenous religions as religions of life with other people, and the kind of pleasure of company, the magic of the spirits, colour.

Alcio ❖ And singing, and being together, and eating together, because most native religions here put a lot of stress on cooking for the gods. Even in private, I sometimes cook for the deities of my clan. I began cooking for this reason, not because I wanted to be a chef.

But when you watch American films, usually the kitchen is together with the living room. In Brazil we call this an ‘American kitchen’. Here, it was separate because the kitchen was the place for the servants, the slaves, the cooks, but what happened was that upper class kids were brought up in the kitchen by the servants. This is where life could be found.

Something that’s not so good, though, is that the sexual initiation of the boys took place in the kitchen. For the women, it was not violent, but it was a violence in the sense of the culture, because the daughters of older women were expected to initiate those kids into sex. It was not forceful in the sense of physical violence, but it was forceful in the sense of cultural violence. Yes, that’s where life was … the bad with the good.

CD ❖ How do you bring these connections with native Brazilian and Lusophone ideas and practices into your sanghas?

Alcio ❖ At first, we would bring images into the temple; the temple now has Indian and Afro-Brazilian images. What we call Afro-Brazilian religion doesn’t exist in Africa, since when Africans were brought to Brazil, and as they were from different nations, they had to build a new religion that would accommodate gods that had never met in Africa.

As for native deities, sometimes it’s really confusing, because there are many myths that would have to be set out as narratives created to explain things. How can you put this god that has three wives, with the other one that has the same wives? It can be confusing, but people do make their way through it.

So we brought in the images and they began mixing – not mixing the ritual of zen with the ritual of the native Brazilian religion, but making them happen in the same place. The ritual is the ritual, but everybody uses the same holy place.

People sometimes use the metaphors and myths of local religions in the context of zen to explain things, and that’s what we call living together. A friend is a Protestant minister who invites priests of the Afro-Brazilian religion to services in his church. They become possessed by the spirit, and the spirits conduct the service in this church. Everything gets mixed up.

CD ❖ This brings to mind the teaching of dependent arising: that we’re all creatures of our conditions, that there are just conditions upon conditions upon conditions, and that we embody all of those in our actions in different circumstances. So often these traditions become reified, though – rituals become dead rather than living embodiments of the present.

Alcio ❖ Well, there’s no reason to create layer upon layer of oppression. I’m not against using Japanese clothing, but in a tropical country, there’s no sense in wearing 13th century clothes. We understand that Dogen Zenji was a great guy, but I don’t have to wear the same clothing as he did to show my respect for him. In the same way, I do not appear in the temple naked, like my ancestors, because it’s a little offensive, but we can be just the people we are now.

In my first years as a zen teacher, I wore traditional clothing and had a bald head. One of the guys questioned this. ‘Why don’t we wear the same clothing as the Buddha, why don’t we stick to the real traditions of the Buddha’s era?’ My response was: ‘Do you want us to sit on the floor? Use a thong and no underwear? Is that what you call the tradition?’ While I was talking with him, I said, ‘Okay, that’s crazy but what’s the sense in wearing 13th century clothing?’ I began questioning everything.

This guy was right, though he was wrong in the beginning, in my view, because he wanted to be more traditional than zen. I thought ‘my goodness, why are we doing that?’ Suddenly it felt like I was dressing for Carnival. I know, this is not very orthodox. Even in Upaya they use Japanese rituals. I spoke with Joan about this. We can understand each other with respect. but I’m not going to take part in this kind of thing any more.

This feels like Stephen Batchelor in the sense of Buddhist translations: when he talks about different translations of the dharma, we see that translations are very culture-based. It’s unavoidable.

CD ❖ This is where creativity comes into our understanding. You spoke about magic, so you know about the importance of joy and magic and pleasure in life.

Alcio ❖ Yeah. When I was studying anthropology, we studied Max Weber. He wrote about the disenchantment of reality, and capitalism, and the Protestant ethic. I liked the enchantment of reality, not for the negation of reality like being anti-vaccine, and things like that. I think of the word ‘magical’ in the sense that we do not really understand everything; things are a mystery.

I work with dying people, and I don’t know that much about death or dying, or living for that matter, and I think magic helps us give a place for things we don’t understand. Everyone in our religion has what we call o pai do santo literally ‘the saint’s father’, but it’s the name of the priest. And a priest in the native Afro-Brazilian religion is called pai de santo. And then every one of us has a pai de santo. My father was a pai de santo, but he was not mine.

In that sense, my pai de santo is a psychologist in everyday life but when he’s possessed, he gives me very fruitful insights about my life, the way I deal with things. And sometimes I even tell my patients to consult him, because I understand that he has access to unconscious things that I don’t, which people may reach through him.

People ask me, ‘Do you really believe that?’. I say I believe in everything, yet I don’t believe anything because everything is a narrative. How can I tell you that the main entity of my clan, Xangô, is the god of thunder and rain, something like Jupiter in the sense, though like Jupiter he likes women a lot?

And how can I say that Xangô exists as this guy who is riding his horse in the sky? Or at the same time how can I believe that Kuan Yin is a woman with eyes of compassion, looking at everybody? These are narratives, and the way people talk about mystery is something we will never know the truth of. I can tell you, I don’t care about the truth in that sense of the real truth of things, except how can I take care of people really, and take care of myself? And if those narratives help me take care of myself and other people, that’s okay.

CD ❖ That’s the pragmatism you spoke about, the idea of being possessed. It seems like a sense of openness to what we don’t understand, because there’s so much deep in our experience that we can’t possibly explain or understand.

Alcio ❖ I think when we do deep meditation, we put ourselves in a state of acceptance in the sense of being open to something that, if I use my psychoanalytic side, I would say that maybe I have unconscious things that come through in this time that I’m not opposing it. Call it unconscious perhaps. I prefer to call it dharma, or Xangô.

CD ❖ You alluded in the Upaya talk to the guest and the host: who’s the guest, and who’s the host? In a way, we’re talking about being a host, inviting the guest in. Just whatever, whoever arrives, be a generous host, and then the roles of hosts and guests become interchangeable.

Alcio ❖ Yeah, that’s the idea. Because traditionally, in zen lore, a guest and host are like teachers and students. In that sense, the student is a guest and the teacher is the host. But the idea is that nobody is a host, or nobody is a guest. I mean those roles can be very fluid in that sense. Because it’s like a dance.

Earlier today I made some necklaces. Each has different beads and cords representing different deities. I then went to a laboratory to be examined by a heart doctor because I’m going to have surgery on my shoulder. The woman who was giving me instructions asked: ‘Oh, can you take off your necklaces for the exam? If it’s not okay, the doctor will make some kind of adjustment, but it would be easier if you took them off because she needs to see your carotids.’ ‘No problem,’ I said, ‘I can take them off.’ It’s part of our rules, and I was in a scientific setting, but of course we have a magical setting too.

I hope the necklaces go with me into surgery. ⁂

➡︎ This conversation has been edited for space and sense

AN ECO-ART PERFORMANCE

‘Suspended states’

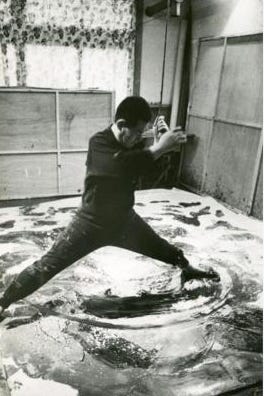

You are invited to the exclusive premier of ‘Suspended States’ – a 20 min eco-art performance that Hartmut Veit will be performing for the first time in homage to Kazou Shiraga at the new Stanley Ave Studio open day on Saturday 2 April from 4:30-5pm (Melbourne, Australia time).

Through the performative restaging of Kazuo Shiraga’s oeuvre, Hartmut will be exploring increasing collective anxieties about the current climate crisis and the looming potential of another world war.

⬆︎ Kazuo Shiraga [Photo https://wikiart.org/en/kazuo-shiraga]

If you’re unable to make it in person, you can see it live on Zoom:

https://zoom.us/j/6459862232?pwd=aGFOUVB1aGlCTWxCcEpPNFV3d3RjQT09

Meeting ID: 645 986 2232 Passcode: zQ1Hiq

This performance is part of the Stanley Ave Studio open day on Saturday 2 April – a whole day of free art and yoga classes, with live music, artisan gelato, life drawing, a painting class demo, and a host of door prizes.

We hope we will see you on the day at 61 Stanley Ave, Mt Waverley in Melbourne. ⁂

ALL THINGS COME TO AN END

This is the final Creative Dharma newsletter

Impermanence – there’s no getting around it, is there‽ And Creative Dharma, a newsletter, which was the focus of the energy of so many people, is no exception. With two pandemic years under our belt, we’ve decided to let it pass away.

Your support and contributions – creative, monetary and otherwise – have allowed Creative Dharma to grow and to flourish. The newsletters will remain online at https://creativedharma.substack.com and if you are welcome to leave comments.

So this is our 15th newsletter, and most likely our last, and here we offer an invitation to each of our 435 subscribers:

If you have the time, energy and inclination to continue breathing life into this project by taking the reins and moving Creative Dharma on into our common future, please reach out and make us a proposal. Replying to this email – we would very much like to see this labour of love develop in unexpected directions.

While the generosity of many has borne fruit, we have switched off paid subscriptions. Some of you will have received a rebate of the unused part of your subscription payment.

The newsletter’s three core contributors – Brad, Ramsey, and Ronn – have also flourished and grown as we brought together the artists, writers, musicians, dharma practitioners, and other creatives who made the newsletter what it is: a dynamic and open platform for the expression of dharma in its many contemporary forms.

And we’re deeply appreciative to all of those artists, representing a broad spectrum of the arts, who contributed their writing, images, reflections, poems, insights, and interviews which gave Creative Dharma its rich texture and depth. The world, we hope, is just a little better as a result of these efforts.

We’re especially grateful to those of you who chose to offer financial support in the form of paid subscriptions. We, in our turn, passed on all of the funds we received as grants to two artists – Jacqui and Hartmut – each devoted to bringing art-making and contemplative practice together for the benefit of their respective communities, and audiences. Your generosity will live on in their continuing work.

In February, we donated USD $200 to Sati Sangha, a secular Buddhist community around teacher Linda Modaro, which is doing superb work introducing creativity to meditation practitioners through the practice of reflective meditation. Linda’s teaching – alone and in conjunction with her colleague Nelly Kaufer of Pine Street Sangha – has opened up new dimensions of practice through contemplative reflection on our actual experience in meditation and everyday life.

Incorporating journaling and quiet retrospection following sessions of sitting practice as well as speaking about the flow and shape of our internal worlds, her approach is in fact a creative space for personal experience to live and deepen.

Linda, Nelly and teachers trained in reflective meditation have provided an hour-long sitting-reflection-and-sharing online venue with guidance and support each day for the length of the current pandemic. Creativity is a vital part of this sangha.

This grant emptied the newsletter’s account of subscription income, and in fact needed to be topped up, which we, the editors, did. You can look through our cashflow …

here.

To view the subscription income flow in, and see where it went, click on the Subscription in+out tab at the bottom.

Readers who wish to offer your thanks, your gratitude, for these newsletters now can do so with a donation through PayPal to generosity@creativedharma.org. We will be very thankful indeed for your dana, and can assure you it will be put to use in appropriate ways. ⁂

Brad Parks and Ramsey Margolis

for Creative Dharma, a newsletter

Evening

It is with some sadness that I read these articles that you have written and published are finishing. Whilst I have not participated actively I have found them stimulating and with some the opening of doors to new thoughts and others confirming my buried thoughts and rebirthing them.

Hopefully from time to time your wisdom and thoughts can still be shared with us all. So often now we sit in our homes without the stimulation of others around us and yet our cognitive development and functions is so dependant on the input from other people.

I do hope as time passes your pens will resurface and delight us all again.

Thank you

Paula