CD#14 Switching off the autopilot of language

February 2022

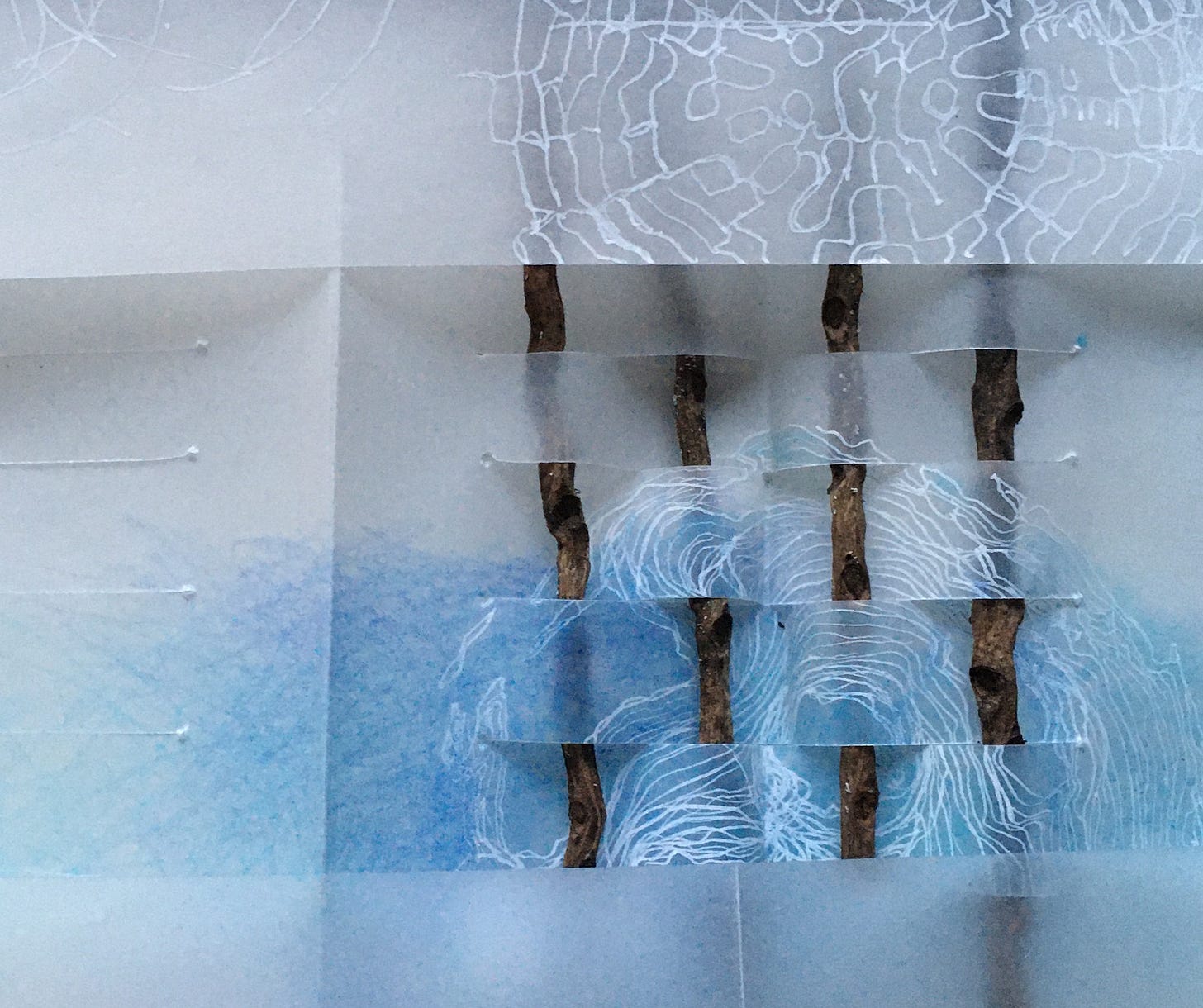

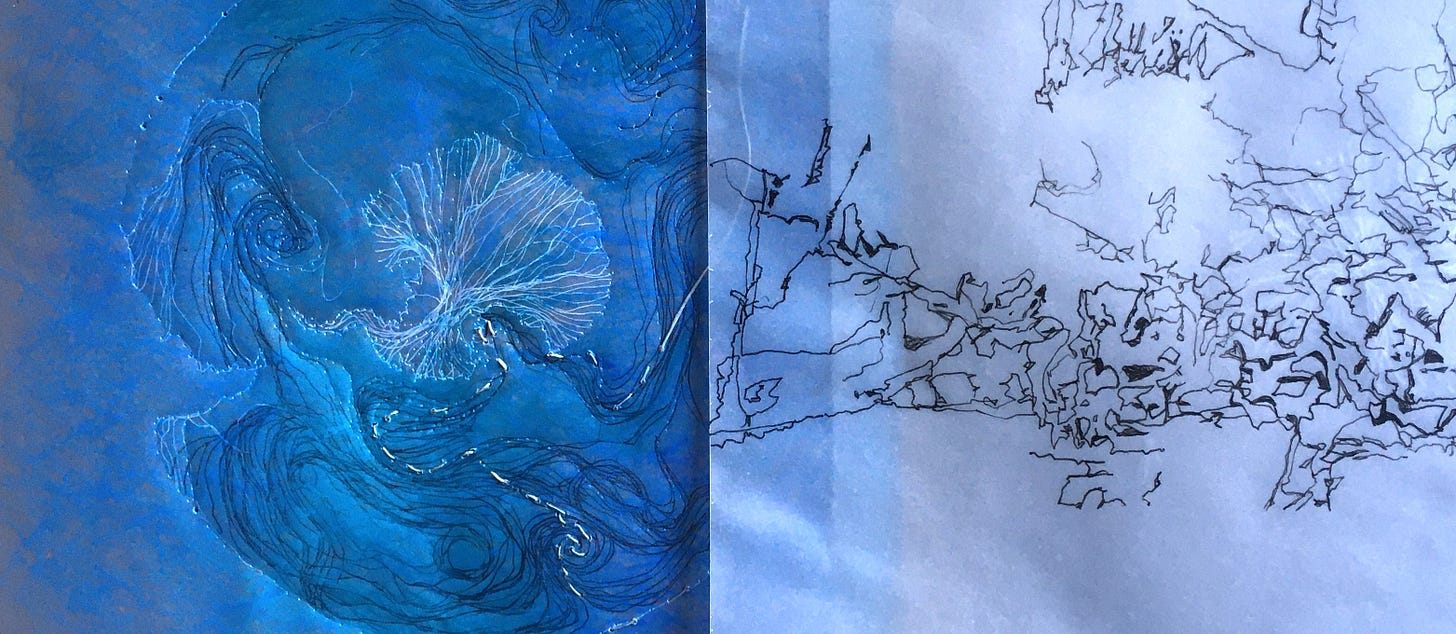

⬆︎ From ‘En las profundidades’ by Cecilia Ramón [photo Cecilia Ramón]

In this newsletter, Barcelona jazz musician Bernat Font riffs on dharma and creativity, poet Bernard Cadogan flies on manual, and ecological artist Cecilia Ramón pulls together the strands of her work while stranded in a small coastal Uruguayan village.

DHARMA AND CREATIVITY

As performed by a jazz musician

by Bernat Font Clos • www.dharma.cat

For ten years, I was a professional jazz pianist and composer. With this background, how do I understand the relationship between the dharma and creativity?

Jazz musicians are constantly responding to changing conditions. We have to be creative all the time because we’re playing for different audiences. We may prepare a song list, but after a couple of songs realise that some will not work with this audience, or in this venue, or because of the sound.

Other musicians bring their instruments to the venue. In my case, I find the piano, but it’s not the one I practice on and every piano is different. So how do we adapt? We have to respond, and in jazz there’s a lot of improvisation, which means we are constantly responding to what the other musicians play.

In an episode of Downton Abbey, a jazz band is invited to the house. Maggie Smith, the dowager countess, tells someone, ‘I wonder if any of them knows what the others are playing’. Sometimes jazz is mocked like this. Actually it’s the opposite: you really cannot play if you’re not listening to what others are playing.

When I taught at a music school, I might stop a band during rehearsal to ask the guitarist, ‘What was the sax player doing?’ or ‘Who just played the wrong chord?’. Since they were so focused on what they were playing, no-one knew how to answer.

A jazz musician learns early on that they cannot be self-absorbed. And you can never complain that ‘it’s not supposed to go like this, they shouldn’t be playing this’, or get annoyed, or plan how the thing is going to go. At all times, you have to start by accepting what is happening at that moment. You then respond in a way that transforms the situation, and affects what others are playing. There’s a lot of experimentation, and this is one of the forms that this activity demands.

What came up for me when I was thinking of the dharma from the perspective of a jazz musician is the role of experimentation in creativity. What’s more, I realise that our life and the world we’re in is like a jazz concert. We never know what other people are going to play, and in a changing and uncertain world, creativity is inevitable. You cannot plan, you have to be creative, to make choices, try things out and see what happens.

Particularly in music, because you cannot undo a mistake. You’ve already played the wrong note. You cannot pause, and you certainly cannot go back. Always, you have to move on from your mistakes.

We live in an uncertain and changing world, which means we embrace mistakes because we can never know the outcome of our choices. We do our best to think things through, but can never be sure. We try things out and see what happens.

Yet there is such pressure to be perfect. We don’t want to make mistakes, particularly as meditators. We complain about what we’ve done, or how we feel, because it’s not how I should be feeling after all these years of practice, I should not have done that. I’m a meditator! When this happens, we are forgetting the need to accept the way things are at that moment, and that we’re in a mentality of effects.

In my late teens and early 20s – and I’m so glad I moved on from this – I suffered from the fifth hindrance: doubt, vacillation, indecision. On my worst days, I could spend 15 minutes in a supermarket aisle because I couldn’t decide which biscuits to buy. My mind would be racing, imagining the alternative futures if I picked the chocolate ones, or the others.

And I never understood why the texts identify discernment as the antidote to doubt. ‘That’s precisely the problem’, I would think. How was discerning supposed to help? Then I saw that a big part of the fifth hindrance is a lack of confidence, of trust. Not only trust in the process and my intuition, but trust that if I made a mistake I will realise that I’d made a mistake, and will be able to do something about it. Now, I consider the antidote to doubt to be ‘confident experimentation’.

Making mistakes could bring suffering, of course, and I suppose that’s why we resist, because if we make a mistake, we may make someone else suffer, or we may cause ourselves suffering, or both. This makes it tricky.

But if we suffer because a mistake we made impacted someone, at one level there’s something good in this. It comes from a good place, it shows that we can empathise.

We can also be creative with the dharma itself. I have a tendency to think the teachings through, ask how I understand them, find my own words and (re)articulate those teachings. While I realise not everyone shares this obsession, it probably comes from my jazz training where one is supposed to not play exactly the same way that others do. Even if you are very influenced by a musician, you’re supposed to give a tune your own spin.

Whether it’s jazz or the dharma, our personal style may not differ that much from everyone else’s. We don’t need to come up with something completely new. One does, though, get used to searching for one’s own voice. Inevitably as a jazz musician that’s the way I practice.

I also play the dharma in my own way. I encourage you to make the teachings your own, and the practice your own. Teachers are there to help you find your own understanding of the teachings through asking the most useful questions, not to push a particular dogmatic interpretation of the dharma down your throat.

We often forget to be playful with the practice, too. This can be particularly helpful when our practice feels stuck. I’m quite playful with my awareness of breathing. Recently, for some reason, I’ve been imagining/feeling my breath as a colour in front of me. This helps me stay with the breath, with the present moment, and it introduces a certain element of imagination and playing with my perceptions.

This relates to intuition, and the way that the Buddhist tradition has tried to articulate this very undefined inner space, inner experience. Even if you don’t know exactly what you’re doing, sometimes you start to relate to the breath differently, or do lovingkindness meditation and feel it in a different way. And suddenly, your practice takes off.

One way that the Pali texts express creativity and imagination is in the figures of the devas, the deities that manifest to a practitioner and which speak to the practitioner, resolving their doubts or encouraging them to meditate. This doesn’t sit well with our naturalistic and rational interpretation of the world: deity, forest, deities, fairies, what’s that about?

Possibly, this is an expression of the dimension of inspiration and intuition in the language of that time, that place, in the same way that the Greeks spoke of the Muses, and how they get inspiration which, as you know, very often feels like coming from outside us.

I’ve also played with lovingkindness meditation and the four immeasurables, which is a type of practice that I had a lot of difficulties with for many years. My way out of this was to experiment, to see what happens if I connect the phrases to the breath, because the phrases were a huge blockage for me – it felt like praying. Suddenly, I started to practice lovingkindness using just my imagination, thinking of people and imagining lovingkindness flowing towards them, or connecting the phrases with my breathing.

These are examples of how one can really be playful with the practice. In fact, the vipassana movement is the outcome of the results of some very creative teachers more than a century ago, particularly in Burma. It’s quite a new ‘tradition’. Nobody really knows where they learned those techniques.

There is a certain danger in experimenting and wanting to be very creative, that one gets lost in this experimentation and goes very deep, or finds the whole thing very entertaining, or maybe it’s just a distraction. We have to guard against these dangers.

But I think of the metaphor of the goldsmith: sometimes one blows on the fire, sometimes one sprinkles water. So, if for a very long time you’ve been sprinkling water, maybe it’s a good idea to see what happens if you stand back and watch, and just see what is the result of what you’re doing? Am I just experimenting and being playful for the fun of it? Or is this working? Does this make the mind more workable and malleable and flexible and fit for the practice, fit for the four tasks?

So this is the test: if it works, use it. ⁂

– adapted from a September 2021 talk given during a Bodhi College Secular Dharma course module

Connect with us on Instagram @creative.dharma

SWITCHING OFF THE AUTOPILOT OF LANGUAGE

Writing poetry requires us to fly on manual

by Bernard Cadogan • bernardcadogan.substack.com

In a recent issue of my newsletter poetry & polis, you will find a poem about the black matipo tree of Aotearoa New Zealand, one on an obscure Uruguayan poet and a famous New Zealand sexologist, and lastly a poem about an exoplanet.

What’s the connection between a tree, surrealism and a ‘hot Jupiter’? Maybe the same sort of connection we find when Lautréamont juxtaposed an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table, and Man Ray made an installation out of that combination.

Poetry has to work with the truth as poetry finds it, not as ideology or critique would prescribe it, and not as science, law or philosophy would require of it. Poetry is also not to be confined by the ego and limitations of the poet. We all have limits, but the poet must not preclude poetry’s possibility of finding itself, in spite of her or himself.

The self that insists it is foundational is a fiction or cultural construct. There are ways out of that naivety.

⬆︎ Kōhūhū or black matipo – photo Tim Entwistle

The kōhūhū, or black matipo, is a plant with an elusive secret. Fragrant all night long from its small black fleurs du mal, it attracts moths and night flies. As soon as light falls on it, though, the scent vanishes. At about seven in the morning in the Spring of 2016, I would stand next to a kōhūhū on the northeast corner of Clyde St and Wairere Drive in Hamilton, New Zealand, and wait for the fragrance to disappear.

This brought to mind the myth of Orpheus turning back towards Eurydice as they were about to leave the underworld, and how she was again lost to him. Poetry is that elusive, and for most of us it uses one of our least developed senses. It takes practice to use it.

Poetry is a process of elimination, and wising up. Dumbing down is bad if we iconoclastically throw the sink and the whole bathroom out the window. There is no point denying that we belong to a wider civilisation, that we have contact with other civilisations, and that our language has its own memory and encoding.

Yet we do have to cut back to arrive at the radical truth of what is being said. The root of poetry is listening. It takes practice to hear the poem rightly. We have to be wise to the tricks that language plays, or else it will predetermine us through a turn of phrase, some narrative, or discourse. Language is great at putting up scaffolding and filling in gaps in all the wrong ways.

Poetry is the recovery of freedom within language. I’ve heard tell of contemporary authors and poets who never read past authors. This is naive. We are the sum of our readings and auditions, the sum of le silence de l’écriture as the French call it. ⁂

– Bernard Cadogan is a New Zealand poet who lives in the UK. He publishes poetry & polis – a weekly Substack newsletter on how to write and read poetry, do politics and geopolitics and think political philosophy – and is the author of the New Zealand epic poem Crete 1941 (Wellington: Tuwhiri 2021); this is a lightly edited version of an article from his newsletter

431 people receive this newsletter, of whom 22 pay for their subscription – click the Subscribe now button to make yours a paid subscription and you will be supporting artist practitioners and secular dharma communities

Coffee

by Bernard Cadogan • bernardcadogan.substack.com

I play floorboards like a muffled keyboard

so my steps do not disturb the night filled

with nothing, and my movements untoward

only bring a coffeepot through the still

house occupied with sleep, to end up poured

into this poem. I managed to spill

none of it on the way past the sword

edged nail that would jab feet pinnacled

in the living room. Cats might play a chord

as they go about but my feet are drilled

to make isolated sounds on the sawed

floor. No one will wake to the doubled

noise of pacing. The truth is I adore

silence. Where I find it present, I will

myself to its observance, and accord

myself to fit in with its intervals.

The sleepers are able to ignore

my daily nocturnal miracle

since quiet is something that coffee hoards. ⁂

¤ 25 January 2022

EN LAS PROFUNDIDES

Cecilia Ramón: Where the line follows

Interview by Ronn Smith

Cecilia Ramón’s artwork is not easy to define or describe succinctly, but ‘ephemeral’ comes close. As she explains in her artist’s statement, ‘My work investigates models of equitable cooperation, our relationship with living systems, and the possibility of living within ecological limits. I develop participatory projects that invite us to imagine a new relationship, with ourselves, with others, and with the living world around us.’

Born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Ramón now lives in Duluth, Minnesota, where she teaches in the Art Department of the University of Minnesota Duluth. Whether she is creating an installation, site-specific work, or drawings, her primary materials are salvaged wood, thread and paper, botanical inks, and stains. ‘Each of these materials,’ she states, ‘offers in their own way a metaphor of the human body and the body of the earth, fragile and strong, subject to gravity and change, allowing me to explore visually the body/mind continuum.’

Ramón and I recently talked about the 11 months she was stranded in La Pedrera, a coastal town of Uruguay with a year-round population of 220; the drawings she made as a result of her daily walks along the shore; and how her Buddhist practice nourished both her and her artwork during that challenging, extended period.

The following interview has been pieced together from several conversations we had on Zoom, as well as from email communications exchanged since we were introduced to each other by a mutual friend early last year.

⬆︎ From ‘En las profundidades’ by Cecilia Ramón [photo Cecilia Ramón]

Ronn Smith (RS) ❖ Let’s start with the basics. Why were you in La Pedrera?

Cecilia Ramón (CR) ❖ My mother and I were there for a brief vacation. When the pandemic hit, the borders between Uruguay and Argentina were closed, and all commercial flights from Montevideo to the United States were stopped. My mother was 86 at the time, and I was 54. We stayed in the same bungalow for five months. After my mother was able to return to Buenos Aires, I stayed another six months, waiting for flights to resume.

I walked along the seashore every day, whether it was cold or windy, rainy or sunny. It was a dialogue with the ocean, which gave me oxygen and strength. Something happened in me there, something happened in the dharma, with my practice. I was able to buy tracing paper at the small shop by the local grammar school, so the series of drawings I made during that period reflect those walks. The series is called ‘En las profundidades’, or ‘Into the depths’.

It’s the first time, Ronn, that I could see how ‘making’ was a natural process, just like the ocean tides. The drawings incorporate layers of transparency. For me they were a way of seeing the ocean both as this incredible force we are a part of and as a metaphor for the human mind. It was truly an exploration of slowing down, seeing my mind, and then responding to this need to make something with my hands. The making was just an impulse of the animal that is my system, which came out of the ocean through years of evolution.

RS ❖ So the walking was a kind of meditation out of which ‘Into the depths’ grew? Was this a new way of working for you?

CR ❖ Yes. Through months and months of walking alone, of touching the sand and waves, it became a meditation of decentering the human species. There was something impermanent in the walking, but in the standing meditation as well. I could look back at my steps in the sand and watch them being erased by the ocean. Back in my tiny bungalow, at my drawing table, I could retrace my steps as an art practice.

RS ❖ There are a number of artists who use walking as an art form, but this doesn’t sound like that, Cecilia. For you, the walking is a process that leads to the drawing, but the walking is not an end in itself. Is this a fair assessment of what you were doing?

CR ❖ I agree. I do some walking-based work, like walking the currents. But what I was doing in La Pedrera was stepping into the unknown … or trying not to name what I was doing. It was more of a retreat practice: feeling the ocean and ground as sangha. I was making the drawings, and then superimposing the tracings. Everything was uncertain. The pieces are very foggy, blurry, like what happens in a camera when you try to focus it. I still don’t exactly know what ‘En las profundidades’ is about. It’s almost like seeing through water, and I’m waiting for the water to go still so that I can see the work more clearly.

RS ❖ But what you describe sounds very much like the meditation process itself, in which we are often instructed not to label what we are experiencing.

CR ❖ I wanted my practice as an artist and my Buddhist practice to be seamless. I don’t have the words for it, but that’s what I was trying to discover.

RS ❖ Is it necessary that you identify, or name, the experience? Is it not enough just to say that it resonates?

CR ❖ It is totally enough, and that was the joy of those 11 months. It was enough, just like the waves or this stone.

RS ❖ ‘Into the Depths’, for me, really reflects the two main concerns you say are threaded throughout your work: the lack of control at the core of our existence, and our immersion in the world of nature. I’d like to shift our conversation a bit, however, and ask about Agnes Martin. She means a great deal to you, doesn’t she?

CR ❖ Yes. She belongs to a different era, but in terms of what art means – and art and the ego – yes, she has meant a lot to me. Her process was totally specific. She would sit and wait for inspiration. She would see an image and then do these incredible mathematical calculations to bring the image to scale.

My work arises in the dialogue of making this line, and another line, and another line. Each one is arising and creating a new harmony, or pattern, or order. So in that way I don’t work at all with an image. My work is in this hand/mind/heart awareness … and a lot of trust in the hand. The hand has breath. The hand moves as the breath moves. As Tim Ingold says, ‘Where the path winds, the bird flies and the root creeps, the line follows.’ In that way the process is very foreign, and very intriguing to me.

RS ❖ Martin’s process was the exact opposite of yours.

CR ❖ Yes. If I would wait for an image, like Martin, I would become a Buddhist nun. That’s okay, too. I have considered it many times. [laughs]

RS ❖ What do you hope people experience when they look at your work?

CR ❖ I don’t think so much about it. If I am faithful to what is coming through in these drawings, I hope they would resonate with other sentient beings. That’s all I can say in my elusive way. Who was it who said, ‘The more local you are, the more universal’? If I can get closer and closer to this life energy, this vibration that is part of our nature, then there’ll be a connection.

RS ❖ So how the work is perceived or received is not your responsibility.

CR ❖ Agnes Martin says that directly. The artist is not responsible for the audience. You have zero control. And that’s true of our Buddhist practice as well. I remember reading Sayadaw U Tejaniya saying something like, ‘The mind is not ours, but we take full responsibility for it.’

RS ❖ Do you have any sense of where this current work might lead you?

CR ❖ I’m not sure how to proceed at the moment. I do want to show ‘En las profundidades’, to share it. I have two ideas that come from gift economy. What would happen if I pin these drawings on the wall, and then let people take whatever they like? Or else I could make a very large one and allow people to cut and take away pieces? That could be documented as the piece disappears, as the pieces are taken.

RS ❖ I particularly like the idea of people removing pieces of a larger work. In some ways it keeps them connected to the work and other people who have participated in the process, unlike taking something from a stack of pre-cut pieces. It calls up many more questions, like: What am I taking? How am I taking it? What does it mean to take it? What remains? What does it leave?

CR ❖ And then there’s all these layers of meaning and metaphor around ‘cutting’ and ‘taking’.

RS ❖ I’m always curious about what influences an artist and her work. What has influenced you?

CR ❖ I have been living in northeast Minnesota for 27 years, so a major influence has been the powerful presence of water in this boreal landscape. Schumacher College, in Devon, England, where I studied in 2015 and 2016, was a key component in helping me develop my ecological, or systems thinking. Other influences would include Latin American poets and my meditation practice.

For me, personally, I am a Buddhist practitioner. My main goal is to liberate this mind of suffering and work for the liberation of all beings. And as I manifest in this lifetime, this moment, I manifest as an art maker.

I make with my hands, which is part of my practice. The making is another way of seeing delusion, of letting go, of decentering the self … the process of becoming not-self. For me there is no division between practicing the dharma, which is nature, and being an artist. ‘Making’ is another practice, another act of becoming nature. The distinction between an art practice and a dharma practice doesn’t exist for me. ⁂

Join the conversation around this newsletter

CLICK or PRESS on the ‘Leave a comment’ button and your message will be posted to this issue of the newsletter; you can also leave a comment on one of the other Creative Dharma web pages – https://creativedharma.substack.com

EMAIL newsletter@creativedharma.org or reply to this email and what you send will be seen only by the editors.

CALL FOR SHORT CONTRIBUTIONS

Focus … Creativity … Generosity …

Dear subscriber, we ask that you write 100 to 200 words for the next newsletter on what these three words evoke for you:

focus … creativity … generosity …

Please send your contribution to newsletter@creativedharma.org preferably by 28 February if possible, but no later than 20 March. ⁂

Thank you, Cecilia and Ronn, for this delightfully insightful and uplifting exchange.