CD#13 Fiction, art, teaching dharma

December 2021

We announce the recipient of the second Creative Dharma grant, report on our October online meeting, and listen in on conversations between Nelly Kaufer and Linda Modaro, teachers of reflective meditation. Plus, Erica Dutton shares observations from a five-day workshop for meditation teachers, and Winton Higgins on the dharma of historical fiction writing ends this newsletter.

CREATIVE. DHARMA. CULTURE.

Supporting Stanley Ave Studio

Recipient of the second Creative Dharma grant, Hartmut Veit is a German/Australian contemporary artist who has been practising meditation for over 25 years. A socially-engaged artist, Hartmut predominately works site-specific with sculpture, installations and performance.

As an experienced meditator as well as being an artist, Hartmut believes it is imperative that we find sustainable solutions that respond to the challenges of the worldwide climate emergency. For him, building community is key: in 2009 he co-founded Melbourne Insight Meditation and is president of this not-for-profit, secular dharma community.

Bringing together dharma and creativity

Working at the intersection of dharma practice and creativity, his current practice looks at how meditation practice and the dharma can help artists be present and engage more deeply with the world through their art. He also examines how creative arts can be informed by the dharma to enable a deeper connection to the natural world, and lead to more wholesome sustainable ways of living.

With this in mind, he has created Stanley Ave Studio, an art, exhibition and performance space that offers regular art, yoga and mindfulness meditation classes, as well as a new, weekly Melbourne insight meditation sitting group.

At Stanley Ave Studio, Hartmut intends to build an inclusive dharma community with a supportive environment that nourishes creativity, research, personal growth and transformation. In essence, it will be a sangha of like-minded artists and dharma friends interested in the modern application of dharma practice to contemporary life and culture.

Within the context of the current climate crisis, Stanley Ave Studio will integrate the imagination and creative arts into contemporary dharma practice as an authentic path to deeply inquire into the nature of the mind and lived experience. The intention is to reconnect and transform our relationship with self, other, and the living world.

⬆︎ Melbourne artist, dharma practitioner and Creative Dharma grant recipient, Hartmut Veit

In addition to offering art, yoga and mediation classes, Hartmut will be inviting like-minded artists, researchers, writers, curators, dharma teachers and performers to present their own projects, in addition to presenting his own art practice and research regarding dharma and creativity. This may include happenings, special events, workshops, day art/meditation retreats and art exhibitions that use the venue for one-off eco-art performances in response to the climate emergency.

The proposed work

He will use the Creative Dharma grant to stage and video document a new eco-art performance within the main gallery/dharma hall of Stanley Ave Studio. Performed in front of a live audience and broadcast on Zoom, the event will be video recorded, edited and later presented online on the Stanley Ave Studio Youtube channel to increase the reach of the initial performance.

This as yet untitled new work and performance will be a homage to the Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, an abstract painter, zen monk and first-generation member of the postwar artists collective Gutai Art Association – a contemporary art movement that was set up in the 1950s.

What does it mean to restage the performance practice of this artist in the time of Covid and within the context of dharma practice?

Through the performance, Hartmut will explore dharma meditation practices and ritual action using his entire body as a paint brush and vehicle to express the relationship between body, mind and matter in order to enquire into how contemporary artistic expression and eco-performances may be inspired by, but also inform a creative and authentic approach to dharma practice.

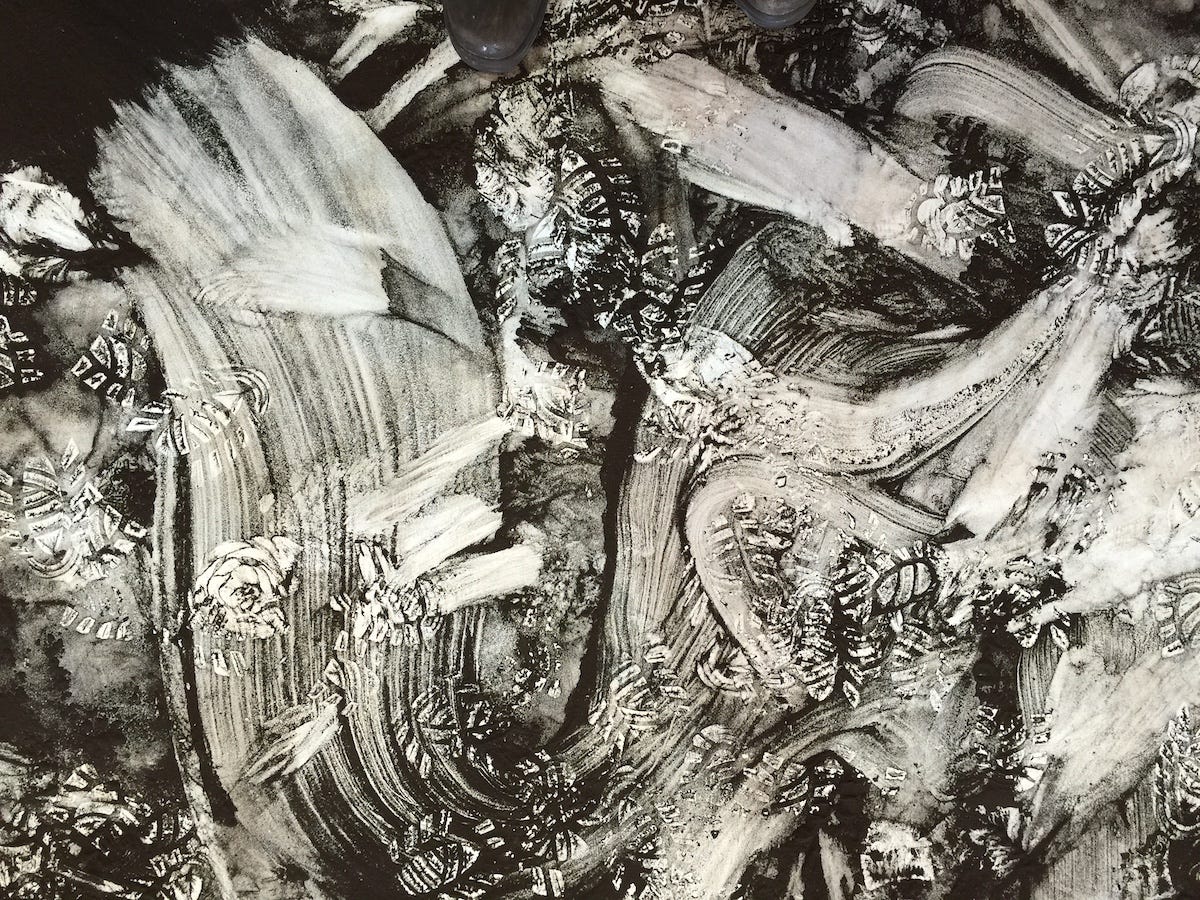

⬆︎ from CoaLounges by Hartmut Veit

He was interviewed for ABC Radio National by Michael Cathcart for ‘The Stage Show’ about an earlier work, in which he employed brown coal as an art medium to question the nature of human relationships with the geological resource material, coal. Their conversation starts 40 minutes into this programme:

421 people receive this newsletter, of whom 23 have chosen to pay for their subscription.

Click the Subscribe button now and make yours a paid subscription – you will be supporting artist practitioners such as Hart Veit, above, and Jacqui O’Reilly, below.

CREATIVITY & CONTEMPLATIVE INQUIRY

Jacqui O’Reilly in conversation with Ronn Smith

The October online conversation between artist and musician Jacqui O’Reilly, recipient of the first Creative Dharma grant, and Ronn Smith, a contributing writer to Creative Dharma, is now available here:

A lively exchange, which attracted a diverse group of dharma practitioners from around the globe, it covered a wide range of topics, including Jacqui’s experimentation with sound, video and installations; her practice-led research for Into the River, a work-in-process about the Te Awa Kairangi Hutt river, near which she was raised in Aotearoa New Zealand; and artistic intervention as a way of addressing the ecological crises of our time.

Jacqui discussed her interest in granular synthesis as a way of deconstructing and reconstructing sound, to enable new ways of seeing and hearing beyond conditioned perception. This concept may be most apparent in Jacqui’s Return from Erasure, a short video work she shared near the end of the discussion.

A free event which ran for about an hour, it concluded with a Q&A from viewers.

DHARMA DIALOGUE

Free-range meditation, with creativity

by Nelly Kaufer (Pine Street Sangha) and Linda Modaro (Sati Sangha)

We are Nelly and Linda, Linda and Nelly. Two friends, spiritual friends. We met during a meditation teacher training retreat in 2005. We both founded dharma communities (sanghas) and have many spiritual friends. Considering our practice a refuge for kindness and curiosity, we practice reflective meditation with a dedicated passion. This involves meditation with reflection and conversation.

The book we are writing, of which this is a lightly-edited extract, will be full of conversations between us. While you’ll hear our voices in the book, you may not always know who is speaking. This is an evolution of our practice, as we become less identified with who said what.

In fact, many times we can’t remember who said something, its value coming from whether it was relevant and honest. We keep cross-fertilising each other’s thoughts, feelings, experience and understanding. We write about ourselves not to elevate ourselves, but to take our teaching out of the abstract and conceptual, and into the nitty gritty of life.

While the reader may not know who is speaking, we do want our names on this book. We believe that most of us need acknowledgement and care when presenting ourselves to others. There are many ways that people can feel hurt by not being given proper attribution, so we follow a middle way between applauding our personal accomplishments and neglecting them.

❖ Conversation one

I know we have both previously collaborated on writing with other folks, but this writing process is so different from what I have done before. A creative ease and flow.

Seems way too simple to say ‘different conditions’ but that is actually how I see it. We set up a time to write and instead of speaking our conversations we write them. Line by line.

We are writing like we meditate: letting whatever comes to mind get written on the page. But we don’t accept everything ‘as is’. Just like we wouldn’t do everything we imagine in meditation. We craft our words to be as clear and skilful as possible.

Yes, this process of meditation carries into our conversations and teaching and now into the written word. The fruits of reflective meditation!

⬆︎ Nelly Kaufer and Linda Modaro in conversation

❖ Conversation two

Why can’t we just memorise the Buddhist teachings?

Memorising teachings has a historical context in Buddhism. It wasn’t till the first century BCE, about 500 years after Gotama’s death, that they were synthesised and written down. One of the reasons the teachings survived was because they had been memorised.

They were memorised because there was no written word. That’s hard to fathom at a time when Buddhist writings fill shelves of bookstores, and are all over the web.

Yeah, it’s like we can’t go backwards – back to when there was no writing, no roads, no electricity… Now we even incorporate writing into our practice through journaling after meditation.

I wonder about that inclination to go back to another time, another culture. I think we need to adapt the teachings to our life now, not the Buddha’s life then.

Though we do have to sift and sort through many translations, and commentaries on translations. Who chooses what comes forward?

They debated about this a lot after the Buddha died. They had council after council – writing down the teachings then revising them. These revisions continue, right up until today.

We are creatively revising the teachings as we write this book.

And an audacity to adapt the teachings to our understandings may be considered watering down the teachings to someone else. Or even blasphemy!

Though I’ve learned the teachings more deeply this way than I had in traditional settings.

Hmmm, does memorising seem the opposite of creativity?

Well, maybe in our approach to meditation it does. There are a lot of lists in Buddhist teachings – the three this, four that, five something else! Dry lists. We don’t expect meditators to memorise these lists.

Though I find the lists useful again and again. At some point, they ground my experiences in the teachings.

One teaching that grounds me is ‘The Four Foundations of Mindfulness/Awareness’ (the Satipaṭṭhāna sutta). This discourse has a structure that is orienting, but gives me room to explore.

Right! It brings us back to being aware of direct experiences, now and with memory.

This teaching helps us become more aware of what’s going on in our body, in our feeling tones, in our thoughts, in our states of mind, in our moods. Along with being aware of the fundamental Buddhist teachings.

Although these categories are segregated in the classical translation, that’s not how we practice. Do you think this is a creative take on this sutta?

Is this because we don’t start with the body, or one of the categories first? Or because we don’t suggest following them in the linear way as written in the sutta? Or because there’s permission to pay attention to moods, feeling tones or anything else in the meditation?

Yes to all. What goes on in our body, moods, thoughts, feelings are interdependent with one another.

This brings something else to mind. What if people haven’t read or heard of this sutta before?

I think they’ll naturally be talking about these spheres of awareness, even without knowing. The spheres curiously and creatively blend together.

And, it’s an attribute of the dharma to realise it ‘each for oneself through our body and mind’. A path will emerge. The path can look so different, and depends on where we live, where we practice, with whom we associate.

– an excerpt from a forthcoming Tuwhiri book, due out in 2022

Join the conversation around this newsletter

CLICK or PRESS on the ‘Leave a comment’ button and your message will be posted beneath the web page for this newsletter; you can also leave a comment on one of the other Creative Dharma web pages – https://creativedharma.substack.com.

EMAIL newsletter@creativedharma.org or reply to this message and what you send will be seen only by the editors.

GLEANED FROM A FIVE-DAY TEACHER WORKSHOP

Nine ways to creatively engage with your meditation practice

by Erica Dutton • ericadutton.com

Take a pause before speaking, relax, attune to yourself and others, and then speak your truth – this is the first layer. The second is receptive listening: what is in the way, preventing you from listening deeply, yet what are your strengths as a listener? The third layer is communicating in groups, and this is always the hardest.

Authority must always be questioned.

Anti-vaxxers are full human beings. They are hurting too. This also applies to anyone who has very different opinions or views from you.

Resistance is a natural part of our meditation practice, and a form of protection. Be aware when it arises in you. It’s a fruitful area for gentle exploration.

Notice the progress/growth you make in your practice as a whole rather than focusing on ‘how you’re doing in any particular sitting’.

Hold restlessness and agitation with compassion for the human experience.

Look at things impersonally. Find the patterns.

All institutions lag behind consciousness.

Suffering and joy can coexist.

– from https://ericadutton.com/2021/11/ideas-from-five-days-of-dharma-teaching

THE DHARMA OF HISTORICAL FICTION WRITING

Like a dancing fairy

by Winton Higgins • wintonhiggins.org

My love of writing has grown over the years. I delight in the way written words act like developing solution on film stock: the experienced world takes on outline, context, and meaning. Without words we’d be like someone trying to work with circles, squares and triangles with no visible lines. Words create meaning out of amorphous sensory experience.

I took up creative writing 22 years ago, and drifted towards the kind of historical fiction which deals with real events of ethical significance, and mainly historical people. Writing and meditation mesh. On a good writing day I can sometimes get into a zone reminiscent of samadhi in meditation.

My first experience of this sub-genre in my twenties was reading Robert Graves’s two novels about a reluctant Roman emperor, I, Claudius and Claudius the god, which are probably where this sub-genre began.

The basic idea is this: you research thoroughly, and never depart from the historical record. But that record only accounts for a tiny part of anyone’s life, especially her inner life, which is why most history books reduce their characters to stick figures. To get a sense of living history we need to flesh their lives out, and we rely on the authority of our imagination to do this. My favourite Australian example is Kate Grenville’s The lieutenant.

But the greatest influence on my historical fiction-writing is Hilary Mantel, both for her monumental recreation of Henry VIII’s fixer, Thomas Cromwell, in the Wolf Hall trilogy, and for her wonderful BBC Reith lecture series on the art of historical fiction, one significantly entitled Resurrection. Our job, as she puts it, is ‘to liberate people who happen to be dead from the archives’. In other words, to resurrect them, placing them back in their known worlds, emotions and mindsets.

Much thought and work goes into this. To take her writing on Cromwell as an example, what was daily life like for early 16th century English people? What reality construct framed their sense of self and what they strove for? It requires real empathy and care for your characters to be able to resurrect them without condescension or supercilious modern judgement.

In the last five years I’ve had two historical novels published: Rule of law and Love death chariot of fire. In both cases I’ve seen the writing as a dharmic practice, and in each case, the subject matter has been ethically significant and challenged my empathetic engagement with central characters.

Rule of law is set amid the first Nuremberg trial of 1945–46. I’d known a bit about the trial from my day job, which involved (among much else) genocide studies. The trial gets little attention in this literature, and I began to think it had been wildly undersold.

The trial crystallised a unique moment between 1944 and 1947 when America was not only the world’s foremost military power, but its foremost moral power as well. Designed by a Pentagon think tank, the Nuremberg trial was programmed to establish a precedent in international law for making the waging of aggressive war the crime of crimes, and making every individual guilty of this or any other crime against humanity personally accountable, no matter who or where they were.

Tricycle editor-in-chief James Shaheen speaks with Winton Higgins about his recent book Revamp: writings on secular Buddhism here:

The pursuit of this ambition was left to 5,000 war-damaged polyglot judges, lawyers, jailers, interpreters, journalists and secretarial staff, assembled in a small bombed-out city with few of the basic necessities of life and work. What a human drama! I chose four members of this ‘trial community’ as point-of-view characters, three of them from contrasting German backgrounds.

The key institution – the four-power International Military Tribunal – inveigled its often recalcitrant functionaries into following its agenda, into a conspiracy of goodness. In this way, I was animating an institution, according it agency.

Love death chariot of fire seemed at first to be a much simpler project. It deals with the last ten years in the life of a British aircraft designer called Reg Mitchell, who died of cancer in 1937, aged only 42. He was a decent, modest man, a keen amateur sportsman who loved his wife, son and garden. Nothing special. To understand why he really matters for us today, I have to introduce a little history.

Three years after Mitchell’s death, in the early stages of the second world war, a relatively small but critical battle took place between Britain and Nazi Germany. It was fought entirely in the air space over Britain. The German air force had four times the number of fighting aircraft than the RAF, and it had the initiative. Had it won, Britain would have been overrun in no time at all, and the war would have ended with the Nazis the unchallenged masters of Europe. We would be living in a far darker world today.

But Germany lost the battle, and ultimately the war. Several factors explain this defeat, not least the ace that the Brits had up their sleeve: an elegant little plane that was faster, more agile and deadlier than anything else in the sky. It wasn’t just an effective interceptor fighter – it became a potent symbol of resistance to pump up public morale and terrify the enemy. German pilots coined a saying: ‘If you see a Spitfire, it’s already too late.’

While terminally ill, Mitchell created the Spitfire. He had already produced a series of innovative racing seaplanes that repeatedly broke world speed records, and he took a dim view of European fascism. Apart from resonating with his increasing physical pain and the horror of impending death, I had to immerse myself in the aerodynamic principles he had at his fingertips. I had to climb inside his head and track the insights and intuitions he followed as he lovingly brought forth his masterpiece.

⬆︎ Photographic reconstruction by Red Saunders for the Derby Museum of Making honours those who, during the second world war, flew the Rolls-Royce Merlin-engined Spitfires that were developed in Derby

As the plane gradually emerged on his drawing board, through the mock-up stage, along to the prototype ready to receive its first test pilot – it seemed to take on a life of its own. It became animated like my account of the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg.

Interviews with people who’d flown Spitfires encouraged me. In the heat of battle the plane seemed to anticipate what a pilot wanted, and executed a winning manoeuvre that he’d only half thought through, some said. Quite a few said that it was so easy to fly a Spitfire because it virtually flies itself. In particularly hairy moments, one veteran said, he’d speak to his Spitfire, and it always replied.

One of the women pilots charged with flying them from the factories to the squadrons described it as flying ‘like a dancing fairy’, and she couldn’t resist performing aerial tricks when she thought no one could see her.

My dharma practice suffuses these novels: care for people – even those ‘who happen to be dead’ – and the empathetic recreation of past contexts would not have been available to me without it.

– from a dharma talk given to Kookaburra Sangha, a secular Buddhist group in Sydney, Australia, on 13 September 2021; Winton Higgins is a member of the Tuwhiri editorial board

Connect with us on Instagram @creative.dharma

A BCBS ONLINE EVENT

Emptiness and form: fiction and the dharma

Led by Ruth Ozeki and Francisca Cho

Sunday 12 December • 19:30–21:00 EST • REGISTER HERE

Buddhist traditions have sometimes characterised the dharma – the teachings of the Buddha – as beyond the realm of language and thought. If this is so, then why have so many Buddhists articulated their understanding of the dharma through literature, in poetry, discourses, plays and fiction?

Might the transformed modes of perception described in doctrinal texts be experienced through literature, through deeply engaging literary texts that blur boundaries between the imaginary, the representational and the real?

Join Ruth Ozeki, Zen Buddhist priest and novelist, and Francisca Cho, professor and scholar of Buddhism and literature, as together they explore emptiness and form, and the many ways that reading and writing literature can teach the dharma.

This event will be on Zoom and closed captions will be available. This event is freely offered, and will be recorded. A link to the recording will be sent by email after the course to those who register. Students will be invited to generously support the teachers and BCBS at the end of the event.

❖ Ruth Ozeki is a novelist, filmmaker, and Zen Buddhist priest. Ordained in 2010 and affiliated with the Brooklyn Zen Center and the Everyday Zen Foundation, she is the author of My year of meats (1998), All over creation (2003), and A tale for the time being (2013). Her most recent novel, The book of form and emptiness, was published by Viking in September 2021. She lives in British Columbia and New York City. Currently she teaches creative writing at Smith College, where she is the Grace Jarcho Ross 1933 Professor of Humanities in the Department of English Language and Literature.

❖ Francisca Cho is Professor of Buddhist Studies at Georgetown University. Her research focuses on the expression of Buddhist concepts in East Asian fiction, poetry and film, looking at the impact of Buddhism beyond formal religious institutions to see how it has given both theory and support to aesthetic media as serious religious practice. She is looking at a Buddhist theory of cinema.

Get the time of this meeting in your timezone here – worldtimebuddy.com