August 2021

A bird’s got to sing by Jacqui O’Reilly, 2020, sound & video installation

In this newsletter, Ronn Smith sits down with artists Emily Harris and John Halpern, Winton Higgins reviews Emergence: the role of mindfulness in creativity by Rosie Rosenzweig, we announce our first grant … and there’s more. ⁂

GIVING IT ALL AWAY

First grant offered

Earlier this year, in March, we asked subscribers to support this newsletter with a paid subscription, promising to give away every $ we receive from subscriptions to those who bring together a creative approach to the dharma with a meditative approach to art.

We intend to give grants to artists, writers, film makers, poets, musicians, and more. We would also like to support events, communities, and individuals that have an approach which fits broadly within the arc of a secular dharma.

Just five months after having sought your generosity, we are pleased to be able to announce our first grant of USD 1,000 to Sydney artist Jacqui O’Reilly. We were impressed with her efforts to bring together essential elements of her contemplative practice through an active commitment to her community, her history, the natural environment, and the values of indigenous culture.

Jacqui writes:

I am an artist and musician in Sydney, Australia. Originally from Aotearoa New Zealand, I have lived here for 24 years. Sydney is located on the unceded territory of the Gadigal people who are the traditional owners of the land.

Currently I use sound, video and installation as critical tools of my artistic practice for intervention in the ecological crises of our time. My installation A bird’s got to sing was exhibited online at the Listening in the Anthropocene Exhibition 2020. This work is a tribute to the silvereye, a bird that is found in both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. In order to communicate and survive, this small bird must sing louder and higher to be heard over urban noise.

For the next six months, thanks to the Creative Dharma grant, I’ll be continuing my practice-led research for a work in progress Into the River. This project is about the Te Awa Kairangi Hutt river where I grew up, the most significant symbol of the beauty of life and existence in my early years.

Sadly, this river and others across the country are polluted with toxic algae due to environmental impact from the dairy industry, which produces approximately one third of the exported world’s dairy products. I hope to increase awareness about this situation through a multimedia installation, and iterate my deep affection for the Te Awa Kairangi Hutt river and the more-than-human world.

I attend Kookaburra Sangha, a secular Buddhist community which meets weekly in Inner West Sydney.

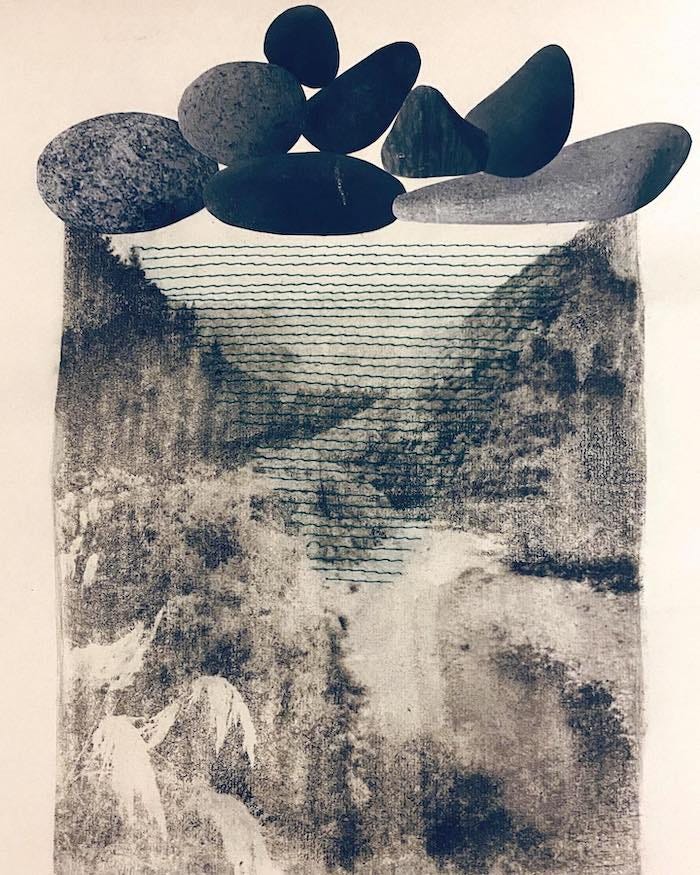

⬆︎ The Sound Rocks Hold by Jacqui O’Reilly, 2021, laser ink transfer of photograph, cotton and collage on rice paper

You can find out more about Jacqui and her work at jacquioreilly.com. ⁂

401 people receive this newsletter, of whom 23 pay for their subscription; click the box below to change to a paid subscription, or to add your email to the list

JOHN HALPERN AND EMILY HARRIS INTERVIEWED

Cultural activism and the contemplative process

by Ronn Smith • Contributing writer

‘If you feel safe not knowing or expecting anything,’ says John Halpern, ‘that’s a kind of art in itself. It’s like meditation meditating you.’

I’m talking with John Halpern and Emily Harris, about the Institute for Cultural Activism International. John is an artist/filmmaker, cultural activist, and educator. Emily is an interdisciplinary artist. Based in New York, they founded ICAI in 2020 to cultivate dialogue, collaboration, experimentation and action among individuals and organizations with an interest in addressing global issues through strategic cultural interventions.

What follows is drawn from our freewheeling conversation on 9 July 2021, during which we discussed art, art making, the contemplative practice, and cultural activism.

Ronn Smith ❖ ‘Cultural activism’ may be a new term for some of the readers of Creative Dharma. Could you define what a ‘cultural activist’ is?

Emily Harris ❖ A provisional definition might be ‘artists who are very grounded in their contemporary reality; who are thinking in a way that is somehow viscerally connected with the world’. Not every cultural activist is a meditator, but meditation can be a part of the process. It also involves ‘transformation’ – the understanding that artists can challenge assumptions and initiate change in society. We’re exploring the nuances of this term through The Tuning Fork interviews hosted by ICAI.

John Halpern ❖ What does cultural activism mean for a tribe in South America or the Sami tradition in Scandinavia? We also want to create some global and fluid meaning for cultural activism within these non-ethnocentric, non-conventionally considered spaces. It’s clear to us that one of our jobs as cultural activists is to activate communities as a bigger force for social transformation.

The work of cultural activism, which in my opinion is not limited to artists, is to analyze the conditions of our ever-changing world and transform those observations through the creation of a new ‘language’ or aesthetic sensibility. In the process, this gives the individual tools with which to recognize their own power and the synergy of collective activity – either as a family or as a community – and perhaps to transform their immediate lives.

RS ❖ What role does the non-artist play in this?

JH ❖ If this conversation is targeted for artists or Buddhists, we’re just involved in some marketing process. Curators need to market their ideas, and historians and scholars need to create ways of talking about this work – all of this is useful in terms of scholarship or fundraising – but marketing per se doesn’t interest me. For me, this is about the everyday person.

I remember Joseph Beuys, in 1977, challenged by a very sincere, middle-aged woman who said, ‘Professor Beuys, you’re telling us that every person is an artist and everything is art. But how should I experience that when I’m peeling potatoes in my kitchen?’ That’s the person we’re speaking to. I hope cultural activism can empower people with a new vision, a contemplative seeing and way of recognizing that we can deconstruct what we think of as problems so that ‘problems’ become more fluid. We want people to think outside the box, Ronn, because there is no box, really.

RS ❖ People are quick to construct boxes.

JH ❖ It’s absolutely a prerequisite for survival in our society, but it’s an ill society when individuals feel they need to fabricate a self, defend a self, fortify the self with opinions and attitude. It’s all a fiction, delusion. That’s what Buddhism brings to the equation: this vibrant sharpness to liberate us from these conditions, traps, patterns, habits, addictions, and so on. Whether we’re talking about traditional Buddhism or secular Buddhism, it makes it possible to flip those concepts of ego, personality and identity so that they become assets in the process of serving the world.

RS ❖ This reminds me of the conversation that is occurring in the secular Buddhist community about creativity, imagination and ethics. It also dovetails with what I’m hearing in discussions on socially engaged Buddhism.

JH ❖ Is there a universal culture? Do all roads lead to Rome?

EH ❖ But I do think certain qualities can be maintained, like empowerment. To empower people takes away that box that we were talking about earlier. You don’t have to defend an identity if you feel empowered. Your actions come from a different place.

RS ❖ I also see meditation playing an important role in this process. John, can you give me an example of a ‘cultural activism’ project, maybe something you are working on now?

JH ❖ Yes, the We Do – Surfing the Apocalypse projects speak directly to the manifestation of creative production and cultural activism/intervention. We’d like to do it in Innsbruck, but we also want to do it in different parts of the world. It’s so simple: people singing together in a cultural context of crisis, disaster and utopian ideas. It involves people collaborating in a loose but structured way, using technology and the ethnic/indigenous roots of a specific place in a performance, or ritual, so that it draws on the transformative energy of the community and location.

⬆︎ Sill from video proposal for Innsbruck, Austria: WE DO: SURFING THE APOCALYPSE / concept for world tour with local and remote performers, moving images from critical global & regional disasters, collaborative – community participatory events. Artists: I.C.A.I. Harris-Halpern.

RS ❖ Emily, I’d like to talk about your Contemplative Outerwear Cap #4, and what generated that idea.

EH ❖ Sure. I’m interested in participatory work involving movement, performance, and site that sensitizes both me and viewers. I was doing a residency at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild in upstate NY where a fellow resident was also a yoga instructor. After her weekly community class, I would go back to my studio and make work. In the studio, I was trying to focus on breath as a material. I saw my baseball cap hanging on the door and saffron colored threads. I started to thread the threads through the brim of the cap, going through the sewn line that was part of the cap’s design. I realized that the altered cap could be used to demonstrate how our speech and song are tactile, how we could become aware of our direct physical connection to the environment. After inviting several performers to perform with the cap, I realized that it was also a visual tool of one’s concentration both inside and outside the body.

RS ❖ In Celebration of 50 Years of Women at Kenyon College, edited by Claudia Esslinger and Marcella Hackbardt, Jae Cho wrote of this work:

The threads simultaneously obscure the vocalist’s face, which may otherwise be the focus of the performance, and reveal the physicality of the singer’s breath in the form of undulating tassels. Whether it is direct or indirect, human presence is a shared feature in [Harris’] work and the viewer is often an unknowing participant. The realization of one’s participation in Harris’ world becomes the realization of oneself in the world at large.

Gordon Skinner’s performance of Samuel Beckett’s Ohio Impromptu is incredible. I respond to it as both theater and as a piece about the breath, which of course relates to our use of the breath in meditation.

⬆︎ Contemplative Outerwear Cap #4 and Gordon Skinner in Beckett’s ‘Ohio Impromptu’ (6:42). Project by Emily M. Harris

EH ❖ I’ll also say that there was a lot of frustration for most of that residency, but it was so productive because I had time to be frustrated and go over the ideas. It wasn’t a reasoned or logical response. It was something that I felt my way through. The yoga opened my body to a place that was more calm, expansive, and which let ideas come in or come up.

JH ❖ What Emily is describing, I think, is the contemplation or the creating of a space in which deep images or fragments of ideas – these ephemeral things – can be seen and, through an intuitive process, analyzed and sustained. Frustration is an important part of the process because it serves as a motivator. Out of frustration comes creative ways of relating to problems or challenges so that we are no longer oppressed or restricted by them. We can relate to or resonate with problems fluidly; we can have a contemplative relationship.

I went into retreat the day the Gulf War started, and my guru said, ‘When you go into retreat, you should think about what you can do as an artist about war.’ That was pretty heavy. I didn’t know at the time that I could use meditation to make better art, to analyze what’s going on in society and come up with a new idea. Out of that retreat came this understanding about greed, which led to a project called New Consume, which received an innovation award from the Swiss government’s Department for Economy and Industry.

RS ❖ Let’s go back to what you said about the artwork growing out of the contemplative process. Is it possible to flip that idea and ask how the artwork informs the contemplative practice?

EH ❖ I started meditating in part because I recognized that I wanted to access these ephemeral, nuanced, difficult surroundings. For me meditation felt like a tool to go deeper into a sensation of the body as well as to become more sensitive to my surroundings.

JH ❖ I asked Martin Scorsese why he made ‘Kundun’, a film about Tibet’s fourteenth Dalai Lama, and he said:

I had to make this film in order to understand why I had to make this film. I didn’t know why I was doing it. And if I knew why I was doing it, I wouldn’t have had to make it.

RS ❖ John, I know you were inspired by Chögyam Trungpa, Joseph Beuys, the German teacher and theorist of art, Martin Scorsese, and Allan Kaprow, a pioneer in performance art, among others. Who inspires you, Emily?

EH ❖ My inspirations are always changing, but right now I would say I’m inspired by Anaïs Maviel, Laurie Anderson, one of my grad school professors, John Penny, Peter Brook, and Paul Chan. And I’m reading Chan’s Selected Writings, 2000-2014.

RS ❖ John, as a meditation instructor trained in the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and yoga, what do you say to young people who – whether they are artists or not – are trying to find their way in the world, maybe as cultural activists?

JH ❖ You’re not giving yourself enough credit for your ideas, but you’re also taking yourselves too seriously. There must be some middle ground where you learn how to listen to those deep, creative voices. But you also need to listen to those voices that are saying you’re not good enough, you’re too young, you don’t count … and take action. If we don’t take action, we won’t learn about our minds and experiences and capacities. So there needs to be fearlessness about taking action and some playfulness in not taking yourself too seriously.

RS ❖ This brings us back to the boxes we discussed earlier.

JH ❖ Our identities are limited by our concept of a self, a ‘self’ derived almost by chance and random conditions. But where we live is outside of the box, impacting family, community and environment. The contemplative process, which is a deconstructive process, liberates us from our habits, from our patterns. It propels us into the unknown and disorients us. It forces us to rely on intuition as the most stable and substantial experience of the here and now.

Intuition is the physical expression of our relation to the here and now. The body is always in the present. You can use breath or any tactile exercise to get into the here and now. And there we can act together. ⁂

Do you have time to respond to one short question about this newsletter? You’ll find it HERE. We really would appreciate your response. Thank you.

POEM

Questions

by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez • ocasiocortez.com

Where are we going?

When birds sing to one another, are they looking for melody or harmony?

I’ve never been the one with answers.

How is it that our eyes betray us?

What does tomorrow bring?

Just questions. Enigmatic, urgent, smoldering questions.

But this, this is a world of answers:

where to go, what do, how to get rich quick –

the degree to make you slick

the title you want to hit

the right dosage for your sick.

Well, I’ve forgotten about the ready-made bullets in that gun

because for me, not knowing is half the fun

It’s the uncertain moment before a first kiss

It’s trying to remember if your seatbelt clicked

It’s the ride.

And I don’t really know about this world full of answers

But I think I’ll hold onto my questions

Because if not knowing is half the fun

Then inventing the answers on a bed of dew drops is the other

I’ll show you the color of my love

or at least I can try

but maybe in that case, two makes better than one.

I just ask that you leave your answers at home

because to be honest, I don’t really care about where we’re going.

I care about who we become along the way. ⁂

The youngest woman to sit in the US Congress, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has been serving as the Representative for New York’s 14th congressional district since 2019. Ocasio-Cortez attended Boston University where she double-majored in international relations and economics, graduating with honors. This poem was posted here in April 2011.

What is this? Ancient questions for modern minds

by Martine & Stephen Batchelor, Tuwhiri 2019

In this book, Martine and Stephen take us through the practice of radical questioning at the heart of the Korean Sŏn Buddhist tradition, and suggest how we can all benefit from this form of meditation today. Find more on this here.

BOOK REVIEW

Cultivating creative processes

by Winton Higgins • wintonhiggins.org

Emergence: the role of mindfulness in creativity by Rosie Rosenzweig, Quanah, Texas: Anaphora Literary Press, 2020, 81pp

This newsletter explores the elusive relationship between spiritual practice and creativity. Sometimes the emphasis falls on the way altered states of consciousness, which can arise in meditation, awaken creativity. In that case, the investigation might extend to the way altered states induced by psychotropic drugs have also seeded extraordinary works of art, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s deathless poem, Kubla Khan. Yet his equally wonderful Frost at midnight seems to have arisen from an ordinary state of consciousness, albeit on a still winter night in a silent room, with his infant son asleep in his cradle beside him. No opium needed!

My own experience as a writer and meditation teacher highlights this second circumstance as the incubator of creativity. Time and again on residential insight meditation retreats, students with creative (pre-)occupations would tell me in interviews – in various states of guilt or excitement – about the way some current project back in the city hijacked their meditation, even in a remote and dedicated dharma centre. An architect absorbing into an intriguing design challenge, for instance.

‘Same here!’ I’d reply. In the middle of a textbook insight sit, my internal editing screen could suddenly pop up and invite me to have another crack at the characterisation – or even just the punctuation – in something I’d written before coming on retreat. I’d give these students the advice I’d received myself: keep a notebook and pencil handy to jot down your illuminations! That way you won’t lose them; and once they’re down on paper, they’re less likely to take up head space.

On the other hand, epiphanies do overtake us, both in meditation and creative practice. Are they necessarily accompanied by altered states of consciousness? And if they are, which way do the causal arrows point? Perhaps epiphanies induce altered states, as much as the other way round. Equally important: where does the inspirational content arise from?

Creative processes

In her short book, Emergence, Rosie Rosenzweig rummages among these questions. A poet, playwright, and academic attached to the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University, she also has a lively interest in modern Jewish spirituality. In particular, she tackles the relationship between dharmic meditation (and comparable starting points) on the one hand; while on the other, creativity in many fields, from dance and photography, through painting, to writing (especially poetry). Her research material mainly consists of interviews with more than forty creatives.

Her gleanings from these interviews about the creative process lend her book distinction. In the artistic practice of each of her respondents, she writes, ‘Buddhist theory can be seen to inform their creative process,’ (p.9). Note the ambiguity in this expression: not all of her subjects are touched by Buddhism or practise meditation (even as broadly defined). No matter: ‘artists engaged in the creative process are either consciously or unconsciously engaged in a form of meditation,’ she asserts (p.13).

Her own grounding in Buddhism includes a teacher-student relationship with Mu Soeng, Scholar Emeritus at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, and interviews with Thich Nhat Hanh and Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche.

Another important influence on Rosie’s work is Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of ‘flow’, which has become part of the positive-psychology canon. She introduces flow as ‘that hybrid state during which creations emerge, problems are solved, and individuals feel at the height of their powers’. ‘Flow’ translates into states of meditation, and is interchangeable with ‘mindfulness’, she writes. ‘It happens just like falling in love’ (p.9). Her central concept – the ‘emergence’ of her title – is also a ‘hybrid phenomenon: the state of creative ideas emerging of their own volition’ (p.10).

The author’s Buddhism

Rosie approaches Buddhism

as a secular system without idols, without the accoutrements of religion, and as a methodology to unleash creativity … Buddha defined a new natural law based on the three qualities of reality: Dukkha (Suffering), Anika (No-Ego) and Annica (Impermanence) (p.15).

This might surprise some dharma practitioners, who are more familiar with the Pali terms anattā (not-self) and anicca (impermanence), which are generally arranged in another sequence – annica-dukkha-anattā – with initial lower case letters. These terms point to significant experiences that insight meditators are likely to have and gain insight from, not to a grand theory of everything. (When did the Buddha ever trade in such wares?) She adduces a number of other dharmic terms, all of them with initial capital letters, and attributed meanings that give one pause for thought.

This book is couched in a breathless tone. It seems not to have had the benefit of the careful reconsideration that comes from creating a second draft, in which dharmic terms could be carefully revisited, refined and deployed more appropriately. True to the idiom of popular psychology and religious texts, concepts have initial capital letters, and thereby reified – made to appear solid and established, but thereby also opaque. By contrast, the dharma addresses us as creatures in flux embedded in life-worlds in which everything is in transition. Its working concepts articulate shifting experiences and processes with no endpoints. Reification does them less than justice.

Towards the end of the book, Rosie concludes: ‘So, the answer to the mystery of Emergence is simple and no mystery: it’s nothingness!’ (p.77). The context indicates that she’s referring to the (post-Buddha, Mahāyanic) Sanskrit term śūnyatā, which is properly translated as ‘emptiness’ (an absence of the distortion and shrinkage of awareness when it’s refracted through the prism of egocentricity). To experience emptiness in this sense is to luxuriate in the fullness of one’s whole life-world. I dare say there isn’t a western dharma teacher alive who hasn’t, painstakingly and often, explained that emptiness does not mean nothingness, as it is commonly understood.

As many of her respondents pointed out, while creating uncluttered periods and places invites in inspiration, it’s not a guarantee of success, or even a precondition to creativity. Great art has often been produced under conditions of chaos and adversity. For instance, someone whose work has inspired me is the mid-20th century American writer Kay Boyle. At a prolific stage in her writing life she was raising six children; she kept a pen and exercise book in the smallest room of her home to continue her creative work in the midst of the turmoil.

Flow and store consciousness

Rosie’s interview material epitomises the essential individuality and idiosyncrasy of creative processes that give rise to art across the board. Her book performs a valuable service in giving the reader access to the divergent creative processes of a range of artists. But the attempt to generalise – let alone theorise – how creativity works may simply lead to mystification rather than penetrating a mystery. On the first page of her foreword she quotes Elinor Gadon: ‘artists really can’t tell you about their process.’

Nonetheless, a couple of big themes in the book call for further consideration. The first is flow. On the purely experiential level, it works for me as a label for the experience of spontaneously finding myself ‘on a roll’ or ‘in the zone’. I can almost hear the whoosh. The mind state itself certainly feels like meditative absorption (think of samādhi, mental integration – one of the eight path factors). As my fingers dance around the keyboard, words and whole sentences appear on the screen, ones that look pretty good but I’ve no idea where they’ve come from. Among other things, my fictional characters can say and do things that astonish me. As the poet Czesław Miłosz put it, ‘a thing is brought forth which we didn’t know we had in us’.

But these unbidden gifts must have come from somewhere. Rosie perceptively suggests such inspirations come from ‘store consciousness’ (ālāyavijñāna in Sanskrit) – a concept that seems to have arisen in the fourth century CE in the Yogācāra school of Mahāyana Buddhism. This area of consciousness houses memories and impressions that are no longer immediately available to the conscious mind, but which can enter it dependent on conditions. Store consciousness comes close to anticipating Freud’s theory of the unconscious.

In sum, Emergence goes to the core relationship between dharma and the artistic creative process that defines this newsletter. It offers a golden opportunity to peek inside the creative processes of fellow dharma/artistic practitioners – inasmuch as they can articulate them at all. But readers would best be advised to rely on their own enquiries as to the meaning of the dharmic concepts it deploys, as you cultivate a personal relationship with your own creative processes.

Get this book through Amazon. ⁂

– Winton Higgins has been a Buddhist practitioner since 1987 and a teacher of insight meditation since 1995. He has been a board member of the Australian Institute of Holocaust and Genocide Studies since its inception in 2000, and teaches a course at the Aquinas Academy in Gadigal/Wangal country, Sydney Australia, on ethical, social and political topics each year. His most recent book is Revamp: writings on secular Buddhism (Tuwhiri, 2021).

CREATIVE DHARMA ONLINE EVENT

Creativity & contemplative inquiry

Join us on Zoom on 16 October 2021

from 4 to 6pm EDT

(North American Eastern Daylight Time)

Artists from the Creative Dharma community will be gathering to discuss their artistic practices, their contemplative practices, and how the two practices intersect.

A recorded introduction from Stephen Batchelor will be followed by a panel discussion, after which Ronn Smith will have a conversation with artist Jacqui O’Reilly, recipient of the first Creative Dharma award. There will be ample opportunity to enter into conversations with other attendees, and put questions to the panellists after that.

While the program is free, registration is required.

➡︎ Register for this event HERE.

To find out when this will be taking place in your time zone click here.

4:00-4:05pm … Welcome by Ronn Smith

4:05-4:20pm … Pre-recorded comment by Stephen Batchelor

4:20-4:55pm … Panel discussion (panellists tbc)

4:55-5:05pm … Break

5:05-5:20pm … Jacqui O’Reilly in conversation

5:20-5:50pm … Open discussion, Q&A session

5:50-6:00pm … Closing remarks

All times above are North American Eastern Daylight Time. Those who want to mingle and talk, share ideas or contact information and more will be able to remain in the Zoom room for a further 30 minutes.

Connect with us on Instagram – @creative.dharma

YOU’RE INVITED TO TAKE PART IN THIS CONVERSATION

CLICK or PRESS on the ‘Leave a comment’ button and your message will be posted as a comment to this issue of the newsletter; you can also leave a comment on one of the other web pages for this newsletter – https://creativedharma.substack.com.

EMAIL newsletter@creativedharma.org, or reply to this email and what you send will be seen only by the editors. ⁂

Beautiful work, Jacqui O'Reilly, thank you 🌱 🌿

Read Walt Whitman’s ‘When I Heard the Learned Astronomer”