CD#02 A painter who meditates

August 2020

In this month’s Creative Dharma, newsletter, painter Scott Vradelis shares his thoughts on his process, there’s a lightly-edited retreat handout from reflective meditation teacher, Linda Modaro, on using creativity in our meditation practice, and a topical poem from clinical psychologist Jan Rudestam.

Also, the third in a series of articles on creative dharma and the creative arts looks at how an approach based on legalistic ethics (a.k.a. rules) may affect our practice, compared with an approach that’s based on situational ethics .

If you find these articles stimulating, we encourage you to leave a comment on the newsletter’s website. ⁂

https://creativedharma.substack.com

ART & DHARMA

Scott Vradelis, a painter who meditates

Introduction

by Brad Parks • Santa Barbara, California, USA • satisangha.org

When Scott Vradelis enters his painting studio, he brings with him many years of meditative practice. His experience of making a mark on the blank surface in front of him has changed over time.

As a younger man he found himself moving with an impulsive speed and his work reflected some of that drama. He had been immersed in an artistic culture which valued spontaneity and action and he took those values to heart.

In recent years, his relationship to his materials and to his actions in the studio have shifted to a slower and quieter dimension where attunement to his own bodily experience guides him. Although he is reluctant to put words to this process, he describes a practice of ‘listening to the forms’ in a way that does not confine what arises for him in static narratives. This is a profoundly solitary activity and demands time and patience.

Each step in his series of creative tasks requires care and deliberation, starting with his preparation of the panels, his working surface. Making a mark on the blank panel can be, paradoxically, both ordinary and exhilarating and comes only with quiet waiting and a deep sensitivity to inward space. His work is embodied in and through his physical posture and he faces the question: ‘What next?’. The paint he applies to the panel opens the possibility of an exchange with the viewer, where boundaries can be discovered and explored in a direct experience.

When we encounter one of his paintings, we are challenged to meet the object in a new way, with fresh eyes, with ‘beginner’s mind’. We are asked to open up. ⁂

Scott Vradelis – This, then That, (for G. Hofmann) 2019

Note on process

By Scott Vradelis • Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA • svradelis.com

When waiting and listening for the forms, the question, ‘what forms to paint?’ shifts to ‘how to paint the forms?’. This corporeal process starts with attention to ‘posture’ (all aspects relative to process), substrate and structure, and goes to media, and how pigmented solutions are applied to a surface.

Attention is paid to the reflective properties of the paint, resulting in a nearly flat surface. When a surface is flat (non-reflective), it creates a vulnerability necessary for engagement with the viewer. Essentially, the form’s surface becomes porous.

Porosity/vulnerability/surrender is required for the exchange of information. The painting is encountered, an experience occurs, that experience causes information to be created. As humans, that information usually gets converted to a kind of story. It’s not necessarily a linear narrative as we typically think of a story (though in some cases it may be), but a story nonetheless. If it generates thoughts, then it’s some kind of story. It’s what our minds tend to do. (Check and see, you are probably creating a story with that information now.)

When engaged with a painting, a piece of music, poetry etc… the challenge is to notice and stay with the experience as it happens, before the story gets generated. Or, notice the story, maybe work with it and do some investigation, but then turn attention back to the experience. What is the object? (The play, the musical composition, the writing, etc…) Can surrender occur? What is this thing?

Creating and sharing artwork can be exactly that. Artists (writers, musicians, sculptors, videographers, performers of all different types, photographers, painters, etc…) all create information (with their commensurate available forms) for others to encounter and experience. A primary form of a painter’s ‘information currency’ is their mark on the surface of the substrate. The information is in the mark, and the overall accumulation of those marks can create the form which carries that information, and information can then generate an experience.

Openings are required for the information to leave.

Openings are required for the information to arrive.

The painting and the viewer each must express a vulnerability, else no fruitful exchange takes place.

—————-

The forms being painted now require a rigid to semi-rigid surface. 100 percent cotton paper is mounted to ½ inch birch finish plywood, or DiBond aluminium composite panels. A small poplar frame is fastened to the back of the panel to help push the panel off the wall, approximately ¾ inch or 2 cm, before mounting the paper to the surface using an archival bookbinders’ glue. A custom gesso is applied to the paper and then the panel is ready for painting.

The pigment is applied with a brush, no tape. Each panel is created in the studio setting. ⁂

We humans were not created for obedience. We are made for creativity, and early on our unbounded spirits dare to sing our own song, our childhood imaginings form original futures in thought, word and deed.

– singer Raffi, in a Huffington Post interview

IMAGINATION

Using creativity in our meditation practice

If creativity is the use of the imagination or original ideas to change our lives and the world, in particular in the production of artistic work, how might we use it in our meditation practice?

Let’s first consider some of the other words for creativity. These will perhaps give us a clue. We might consider inventiveness, imagination, innovation, originality, artistry, inspiration, vision, initiative, or perhaps resourcefulness.

◼Imagination

By allowing the mind to wander during a meditation session and to reflect on what went on afterwards, we become more familiar with our own inner world and are able to learn from the drifting, dreams, fantasies, and unexpected states of concentration. This approach is reliable and trustworthy because we are not trying to fit our mental processes into a pre-existing formula, rather experiencing them as they arise naturally.

◼Original ideas

When things fragment or fall apart in our experience, they can be put together in new and original ways. What is new and original at one point, though, may well become stale, overused, solidified, and eventually die out as time passes. Original ideas may be provisional, but they can serve as inspirations for creative modes of expression in a wide variety of media.

◼Innovation

Necessity is the mother of invention, we are told. This is also true of innovation. Thoughts, feelings and sensations in meditation can be approached from a range of perspectives. Reflective meditation is a creative approach that allows our perspective to change and shift in spontaneous and unpredictable ways.

◼Individuality

A personal understanding of the concept of conditionality depends on our individual capacity to reflect on our past, present and future as these dimensions of experience take form. Finding ourselves located in a particular time and place, with our individual history and aspirations and yet commingling with others, we are able to glimpse our shared human conditions.

◼Vision

If we try to focus exclusively on the present moment, we run the risk of dismissing the past and future as being of no value. Yet we all know in our hearts that we are immersed in the flow of our personal inclinations and associations, immersed in our relationships, and in the historical moment. Our vision in meditation can be broad, open and inclusive, grounded in the complexity of our experience.

◼Resourcefulness

Using a creative, non-formulaic approach, each meditator’s resourcefulness is validated. Bringing our lives into our practice, we value our concerns and misgivings as relevant, while at the same time developing and valuing our personal resourcefulness. We draw from the deep well of our internal resources for each choice we make, correcting our course as new situations arise through the trial and error of everyday life.

◼Inspiration

Seeing what develops over time in our practice is inspiring. Listening closely to the stories others tell when they describe their experiences in meditation in their own words allows us a broader perspective, a humbler view, a more intimate sense of what is possible.

And during hard times such as these, we are inspired when others listen with that same careful, receptive attention to what we share of our own inner world.

We are alone with others.

Practising meditation with a reflective approach helps us develop some of these more challenging aspects of creativity:

openness to and curiosity about our inner life

preference for and comfort with complexity and ambiguity

unusually high tolerance for disorder and disarray

the ability to extract order from chaos; independence

unconventionality

willingness to take risks

introspection, increased self-awareness, including a greater familiarity with the darker and more uncomfortable parts of ourselves.

Developing qualities such as these may also encourage an intense inner drive to create.

Creative people have been shown to demonstrate the ability to juggle apparently contradictory modes of thought, such as the cognitive and the emotional, being deliberate and spontaneous, or both rational and poetic. Imagination is at the core of human experience. Three of its principal components are:

a) personal meaning-making;

b) mental simulation; and

c) perspective-taking.

Our imagination enables us to construct meaning from experience, remember the past, envision how the future might look, step into another person’s perspectives, understand stories of all kinds, and reflect on mental and emotional states – both our own and those of others.

Imagination dwells in the moment, draws from the depths, and finds expression for the riches found there. It touches the past where it discovers seeds for a creative future, or it may rest quietly in a still and quiet moment which itself gives birth to something new in the next moment. It provides those deep connections which bring us together and allows for the development of human understanding and compassion.

– It’s not always easy to track the sources that influence our creativity. In this case, Brad Parks and Ramsey Margolis reworked Linda Modaro’s adaptation for reflective meditation practice of an article by Carolyn Gregoire and Scott Barry Kaufman (authors of Wired to create: unraveling the mysteries of the creative mind). ⁂

THREADS

Sharing our personal narratives

How do you bring elements of creativity into your meditation? And if you create art, how do you bring a meditative sensibility into your practice of creating art, whatever medium you use?

We invite you to respond to these questions, and also to respond to those who’ve previously added their personal narrative to this thread. The first personal narrative, by Ellen Stern, has been added. Do please add yours, and let’s see where this journey takes us.

Please note: to be able to post a comment, you will need to be a subscriber.

POETRY

Breath

By Jan Rudestam, Santa Barbara, California, USA • earthdharma.net

There’s a Zen story about a young monk who complains that it’s boring to watch the breath. The teacher pushes his face into a basin of water, holds him under. ‘Is it more interesting now?’ the teacher asks the gasping student.

Breath is dangerous.

The pandemic spreads in the breath of strangers

without masks, not keeping their distance,

running, panting.

Oxygen mask, ventilator, no use.

Breath is a battle-cry.

I can’t breathe! my face on the grimy pavement,

the policeman’s knee on my neck, my life worth $20.

How do I say goodbye to my brother, my children?

Will they ever be safe in their skin?

Breath is necessity.

The Amazon basin, the lungs of the world,

on fire, to satisfy the burning greed of the rich and powerful.

I gasp, turn off the news, avoid the media.

I already know what’s going on, headed for ruin.

Breath is my practice.

My mind makes lists and plans,

flits from one worry to another,

yet my breath is here when I return.

At low tide, I walk as far as I can,

as far as my breath will take me.

Artwork by Jan Rudestam

Jan Rudestam is a clinical psychologist who is completing an eco-chaplaincy program in which she and her cohort have created art rooted in meditation and a concern for our environmental crises. Their work can be seen at www.earthdharma.net. ⁂

Beginner’s Mind

Focussing on the threshold between creativity and mindfulness, Beginner’s Mind is a monthly newsletter is put together by Christian Solorzano, a designer, photographer and writer who lives and works in Chicago IL, USA. To find out more and subscribe – we have – go to:

https://beginnersmind.substack.com

CREATIVITY IN MEDITATION, CREATIVITY IN THE DHARMA

Morality, ethics, and creative dharma

– The third in a series on creative dharma and its connection with the creative arts

By Ramsey Margolis • Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand • www.tuwhiri.nz and

Brad Parks • Santa Barbara, California, USA • satisangha.org

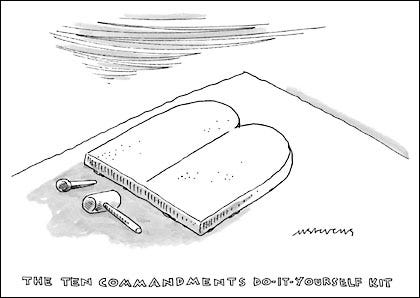

Commandments, rules, precepts … if like one of us you were raised in a Jewish family you may have been brought up to obey the one God and His 10 commandments (note Initial Capital Letters), as well as the 613 laws in the Hebrew Bible, perhaps. Other religious traditions have their own prescriptions, of course.

A creative approach to the dharma has no commandments, nor are we expected to follow five, eight or ten precepts, or 227 rules … oops, sorry, male monastics have 227 rules while female monastics have 311.

The path before us is open.

An absence of rules sounds risky, even dangerous – anything could happen. What’s at the heart of this approach? Where do we find firm ground?

Rather than using rule-based morality to guide our behaviour, what we might describe as legalistic ethics, a creative approach to the dharma suggests that we develop our understanding of causality, of dependent origination – that all phenomena arise in a dependent relationship with other phenomena: ‘if this exists, that exists; if this ceases to exist, that also ceases to exist’.

In this context the ‘conditions’ of our life – our historical moment, our personal past, our cultural environment, our values, our relationships, our roles in the larger world — all come into play. We are both embodied and socially embedded.

From this way of looking at the world, we develop situational ethics, an ethical practice grounded in the situations we face from moment to moment. Rules are inadequately flexible, far too general and not nuanced enough to address our changing world. And they cleverly avoid holding us accountable for our choices. One ‘strong recommendation’ – let’s not call it a rule – might be: put in time developing a meditation practice in which you try to understand what’s going on, to fully know what your experience presents to you, in a direct and honest way.

Someone who came to the One Mindful Breath community in Wellington a year or so back had searched the group’s website ‘looking for the catch’, he said. This is the catch: it’s not enough to read a book, join a community, sing from the same hymn book, pay your dues. If you want a meditation practice that will enrich your life, you will need to put in gentle but persistent effort.

Like any creative art, creative dharma is a practice, but when we try to do it by the book – when we squeeze our internal world into a prescriptive formula – we will have abandoned our fundamental creativity. Let’s look at this more closely.

More often than not, when we are initially drawn to meditation, it’s because we want to stop all thought. We imagine that if we can only just lock up our ‘monkey mind’ in a cage, then tranquility and wisdom will automatically follow. Trying to banish mental activity, we discover, simply doesn’t work. Rather than try to put a lid on the mind, or ‘ban the brain’ as one mindfulness teacher put it, we can practice meditation with an open awareness, in which we neither push away nor cling onto thought.

We allow our experience to arise and with a gentle effort attend to it, an expression of Gotama’s middle way. With time, though, we may learn that our thinking, our emotions, our impulses are signs of human life. We enter more deeply into this life.

Recollecting and reflecting on habits and thought patterns which have arisen during our practice, noticing memories and feelings, we practice the art of befriending ourselves, acknowledging whatever arises in the mind. Our intention is to be gentle, generous and curious, neither avoiding nor clinging to the various threads whose warp and weft make up the rich tapestry of our experience.

Will stillness arise as a result? Yes, and in surprising ways. Completely counter-intuitive, this sounds impossible and certainly feels hard when we first try it. But it works.

This is our truth claim, and no, you don’t have to believe it. Try it for yourself. Over time you’ll see whether it works for you, or not. That’s why it’s called practice.

There’s a word in Pali – sati – that can be rendered into English as recollection-with-mindfulness, or perhaps presence of mind. The opposite of sati may be forgetfulness, or absentmindedness. As in German, which has many compound words, recollection-with-mindfulness is what we’re doing when we meditate on whatever arises with an open and receptive attitude. We remember to show up for our inner world as it appears.

However, just being in the moment is not the be-all and end-all. Practising mindfulness in this way opens us up for honest self-reflection. Of course there’s no guarantee we’ll use these openings in a creative way. Think of the mindful sniper, getting better at their work one bullet at a time.

Meditation can be approached as a technical problem to be solved, or from a commitment to an ethical way of being human in this fragile world, on the eightfold path.

In our view, this, shows why it’s so important to journal – or, at minimum, to quietly reflect – after every meditation session and, with perhaps a month’s worth of entries to then examine the patterns of our feeling, perception and thought. Questions will arise; you’ll want speak about them with someone in your dharma community. (Or get in touch with us, we’re happy to refer you on.)

This practice is one in which we develop a way of being in the world that is relational, guided by situational ethics and creative at its very core.

In short, creative dharma suggests we take responsibility for engaging with our mind, in its broadest possible meaning. It’s one way in which we can live an ethical life, deciding in each moment what is appropriate, and what is inappropriate, drawing on the honest and mature self-awareness made possible by our practice in a community of spiritual friends.

And how better to develop an ethical life than by getting to know the mind, letting thoughts, memories, feelings just be, in time growing beyond the dictates of habitual reactivity with which we injure ourselves, and others. Rather than reacting unskilfully to the situations in which we find ourselves, particularly the difficult ones, those encounters closest to home, we respond from a place of stillness, from the ‘pause’ moment.

To be honest, having tasted the fruits of this work we wouldn’t live any other way. ⁂

… the financial scandals date to a time, before the crisis, when there were ‘few ethical rules for politicians, no rules or regulations on how you present your interests,’ she noted. ‘That was astonishing, but it’s no longer the case.’

Beyond that, though, ‘I look at it pragmatically, not moralistically. I think, “We’re here now, we need to change the system, so we need everyone at the table.” Not, “I’m not going to work with you because you did things I think are morally wrong”.’

Codes of ethical conduct ‘don’t work like normal legislation’, Jakobsdóttir insisted. ‘They work because everyone sits down together and says, “We need to work rules out for ourselves.” And then they need to look carefully at how well those rules have worked, which we’re now doing.’

– An excerpt from ‘Iceland’s new leader: “People don’t trust our politicians”,’ The Guardian, 9 Feb 2018

After Buddhism: exploring a secular dharma

An online course led by Creative Dharma contributor, Lorna Edwards

Starting 10-16 September – find out more about this here.

Do you have a friend who might find this newsletter of interest?

You may wish to suggest that they subscribe too.

LETTER

I

I very much look forward to receiving your newsletter, and possibly participating in the community you are building.

I’ve been a dharma practitioner since 1999, and became interested in dharma and creativity when I was one of several people to organize a conference on the topic for Barre Center for Buddhist Studies (Barre, MA) in 2016. I continue to have a deep interest in how these two ‘practices’ (the practice of dharma and the practice of creativity) intersect and often inform each other.

Currently, I am producing an opera about Gotama and his lifelong struggle with Mara. MARA: A CHAMBER OPERA has a libretto by Stephen Batchelor, the writer and teacher known for his secular approach to Buddhism, with music by Sherry Woods.

We presented a workshop production of the opera in Florence, South Carolina, in 2016, a concert version of the opera using three singers and seven instrumentalists at the Rubin Museum (New York) in 2017, and earlier this year presented three scenes in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

I would greatly appreciate connecting with people in the opera/music/theater community.

Again, thank you. I especially look forward to receiving your newsletter.

Ronn Smith, Cambridge, MA, USA • send an email

Take part

You are invited to take part in this conversation. Either:

• CLICK or PRESS on the ‘Leave a comment’ button and your message will be posted as a comment to this issue of the newsletter; you can also leave a comment on the web page for this newsletter here:

https://creativedharma.substack.com

• EMAIL newsletter@creativedharma.org, or reply to this email and what you send will be seen only by the editors.

• COMMENT on one of the threads on the website. ⁂

Right then, that’s it for this one. Please write and let us know what you think of Creative Dharma, a newsletter and what creative dharma (the notion) suggest to you.

Is there anything you’d like to write, or you’d like us to write about? What would you like to see in future newsletters?

Expect articles in future newsletters on how we might engage with author Philip Pullman’s views, interviews with more artists who meditate, and heaps more.

You can send your feedback to newsletter@creativedharma.org and share our content on social media (we’d appreciate it if you would). We look forward to being with you again in a month from now. ⁂

◼